Volume 4 No. 1 – July 1, 1931

All material courtesy of the National Park Service.These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1931

Come up the mountain to Crater Lake and behold the limpid deep blue of the waters in their varying moods! To you who have bided a time on the rim or have followed the trail down to the water’s edge; to you who have scaled the nearby peaks and communed with the birds and the flowers — we know there is a call beckoning your return again and again.

The same sense of awe which strikes one spellbound when he first views Crater Lake will recur. The mystery of this lake of lakes creates an undeniable urge to return as opportunity may permit. As the views vary from hour to hour and from day to day, they vary from season to season as the angle of light changes with the movement of the points of sunrise and sunset northward and southward along the horizon.

To the visitors of past seasons as well as to those who will come up to Crater Lake for the first time, we extend cordial greetings. This season the roads were cleared of snow so that visitors came up to the rim as early as April 1 — the earliest date in the history of the park.

Camp fires are dotting the base of the moraine and nightly there are many at the Community House and the Lodge attending the lectures concerning the natural phenomena of the park.

In this issue we wish to introduce the members of the Educational Staff for the 1931 season.

Mr. Earl U. Homuth, who has served splendidly in the naturalist service in the past, is again a member of the force; Dr. W. Layton Stanton, Jr., from California Institute of Technology and Mr. Lincoln Constance, a graduate of the University of Oregon, who is engaged in graduate study in the University of California, are beginning their activity in a particularly enthusiastic and efficient manner.

This promises to be the season which will bring a record number of visitors to be inspired and recreated by our majestic scenery and climate.

Birds

By Don C. Fisher, Park Ranger

A list of birds seen in the park has been kept and added to from time to time as a new bird appeared in the park area until last year the number of birds seen in the park was seventy-six. Already this year a stranger has been added to the list. The latest addition being the Mourning Dove (Zenaidura macroura). The dove is essentially a bird of the fields and how they have drifted into wooded areas of the park is a question that is both interesting and surprising.

Members of the various crews have reported many nests of the Ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) and also the Sooty grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) more commonly known as the Blue Grouse.

Perhaps the most unlucky of the forest residents of the park is a pair of Mountain Robins who have resided at Annie Spring for a number of years. They have selected a tree near the spring for the site of their nest and each year have reared their brood. Last summer one of the rangers on duty heard the birds making a great commotion and walked over to the tree. The birds were all a flutter and would hop from limb to limb and then swoop down at something that the ranger could not see. Finally the ranger began to climb the tree and just as he reached the nest a frightened pine squirrel scampered down the tree and away to another clump of trees. Several times afterward the squirrel was soon going or coming from the nest.

This spring the two birds, undaunted by the tragedy of last summer, returned and again took up their home in the same tree. All went well until one morning a great noise arose in the vicinity of the nest and on examination the ranger found that a large raven had settled near the nest and was attacked by the robins who forced it to leave but, however, no sooner did the parent birds return to the nest than the raven swooped down to the nest and seemingly unmindful of the robins, robbed the nest and departed. Thus the law of nature takes its course and the rangers wonder if the robins will return again next spring.

Of the seventy-six birds known to inhabit the park, only five care to stay here the year round. During the summer months the woodlands ring with the songs of the feathered inhabitants but when the old man winter comes creeping into the trees most of the songsters depart for lower elevations.

The five who are here all winter are Stellar Jay, (Cyanocitta stelleri), Oregon Jay(Perisoreous obscurus), Raven (Corvus corax)), Clarks Crow (Nucifraga columbiana),and the Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis).

In the spring the first of the migrants to return are Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus), Western Robin (Planestincus Migratorius propinquus), Mountain Blue Bird (Sialia currucoides),and the Oregon Junco (Junco oreganus).

Carbonized Wood: An Index From the Past

By D. S. Libbey

Recently there have been found several large logs which are completely buried under an overburden of volcanic tuff and agglomerate. Some of the logs exceeded fifty feet in length and they were found resting in a horizontal position without any evidence of roots or stumps. Also there were no small branches attached to the logs but several small branches found detached indicative that both the logs and the smaller branches had probably floated to the place where they were subsequently covered by the heavy burden of volcanic material. The depth at which these logs were found in the volcanic tuff varied from 22 to approximately 60 feet with the conditions thoroughly indicating that there had been no disturbance since the time of their entombment.

The site of this find is about 23 miles directly west from the Rim of Crater Lake along the banks of the Rogue River where excavation by a steam shovel is being made on the now Diamond Lake Road just above Union Creek. The carbonized wood is unquestionably found in-site and the volcanic material – ash and pumice – apparently at some time in the past had completely dammed the Rogue River and caused a reservoir or a lake to be formed. Subsequently the Rogue has worn its channel through the deposit of fragmental material and is now resting upon a vesicular lava rock.

This material has an exceedingly interesting story to tell. The material was buried under a thick overburden of consolidated volcanic ash and pumice and is completely turned to charcoal. The logs necessarily were entombed under very thick loads of hot ashes and the heat, coupled with the rapidity in which the volcanic ejecta fell, resulted in the oxygen of the air being excluded which is essential to prevent combustion of entombed wood. As a result the wood material was changed to carbonized wood or natural charcoal. Such material is capable of preservation indefinitely and its presence can be discovered even thousands or even millions of years later.

The presence of charcoal buried in the midden heaps where prehistoric man abided is one of the most certain means to prove the existence of early human habitation. This is mentioned in order to illustrate the degree to which charcoal is indestructible under normal conditions and that it is such a splendid time marker by which the record of the past may be read.

The carbonized wood being buried under volcanic ejecta, ashes and pumice necessarily forces the conclusion that a very terrific volcanic explosion occurred to bury and carbonize the logs. The fact that the logs were changed to natural charcoal forces the conclusion that the ash and pumice was still exceedingly hot when it came to rest. The volcanic tuff was found in several places to be interbedded with water laid sand and gravels of a heterogeneous nature, suggesting a lake deposit in which glacial material was deposited and also the very definitely cross-bedded strata suggest off-shore conditions.

A complete assortment of the material is being preserved and a record being made of the essential facts concerning the find, so that we may correlate this find with subsequent discoveries of fossil wood, carbonized vegetation or any other material which may be subsequently found. This will enable the scientific investigators to piece together a coherent story concerning the origin of Crater Lake and possibly lend more data to prove or disprove the several theories which are prevalent concerning the destruction of old Mount Mazama. Did the cone of Mount Mazama collapse and then subsequent eruption build up the three volcanic cones now found within the caldera? Did a terrific explosion blow of the top of Mount Mazama, leaving the gigantic caldera which Crater Lake occupies and subsequent eruption build up the volcanic cone of Wizard Island and the two smaller cones which are of insufficient height to protrude above the water level of the lake?

Did the volcanic ejecta, ash and pumice, which buried the logs and changed these to charcoal, come from the eruption of Mount Mazama prior to its final collapse or explosion? Did the ejecta come forth at the time of Mount Mazama’s final destruction? Is the ejecta in question the explosive material of some adnate volcanic cone rather than material erupted from Mount Mazama? All of these questions are easier to ask than to answer. In our small way it is our hope to accumulate the evidences of the past as we are able to discover them and thus be able to piece together the correct story by eliminating the less probable hypothesis.

Beavers in the Park

By D. S. Libbey

This season we are delighted to learn that within the area of Crater Lake National Park we have living colonies of the American Beaver (Castor Canadensis Pacificus), the national emblem of our sister nation to the north. It is the largest rodent on the continent and a member of the squirrel family which as adapted itself to life in the water.

Mr. Fred Patton, one of the oldest employees of Crater Lake National Park, called our attention to numerous beaver dams and fresh beaver cutting along the west margin of the park in the vicinity of Copeland Creek. Mr. Patton discovered the beaver activity while engaged in his work of opening a motor way.

Specimens of the fresh beaver cuttings have been placed on exhibit in the Community House and it is the plan to have guided motor caravans conducted to the scene of the activity by the ranger force. Also very careful efforts will be made to have the area adequately patrolled to preserve the colony of beavers and to prevent their extermination by poachers in the subsequent trapping season.

The pelt of the beaver is connected with the earliest exploration of North America, and fur trading in the days of the Old West was carried on extensively. Vast areas were discovered and developed because of the powerful incentive to seek out the beaver and obtain his pelt.

It is our goal to preserve our beaver friends. Their works have never ceased to be of perennial interest to man. So extensive the dam, so large the trees felled by no other tools than their chisel-like incisors, and so great the tracts of land flooded by the dams that the beavers have become known as the emblem of industry.

A beaver dam is never complete. The busy colony is constantly repairing it, adding fresh cuttings and shifting driftwood, stones and earth so that they are inextricably piled together. The obstructions create the pools of still water so desired by the beaver, and the cuttings from last winter show clearly the snow levels at which the animals were able to work.

The series of dams has materially changed the erosional activity of the creek and has resulted in basins which are splendid reservoirs for catching and preserving vegetable life which slowly decomposes and yields the necessary humus material. This results in offering favorable food supply for a more vigorous growth of flowers and trees which find their ideal habitat in a swamp.

The series of beaver colonies was found about the 5,250 foot elevation in the park.

A Challenge

By Frank Solinsky, Park Ranger

It is the ambition of most persons and corporations to hold a distinctive record of one kind or another. Nature has amply provided Crater Lake National Park with abundant material which, we believe, surpasses any similar phenomena to be found elsewhere. To continue in such a braggart tone is not congruent with the policy of the Park Service. Therefore, with an assumed modesty, we make public the facts concerning a gigantic tree.

This tree, a white pine (Pinus monticolae), stands in the east slope of the Middle Fork of Annie Creek. Measurements were taken in accordance with the Spaulding rule as provided in their log tables and revealed the following figures:

The circumference, breast height – 28 ft. 2 in.

The total height – 140 ft.

The tree is probably about 1,000 years old.

The Middle Fork, as do the rest of the creeks in the park, runs through a deep water and wind eroded canyon. The great age of this tree provides an unusual opportunity for the study of this erosion. The roots of the tree are well covered by soil and there is no indication of ground creep. On the other side of the canyon, we find trees in various stages of subversion. Some have toppled down into the creek below while others, with their roots exposed, have the appearance of standing on stilts. The curvature of some of these trees indicates the presence of ground creep. The one-sided erosion of the canyon can be attributed to the creek which runs under the west slope.

The Location of Crater Lake National Park

By Earl U. Homuth, Senior Park Naturalist

When William G. Steel (Father of Crater Lake National Park) first came to the lake in 1885 he made the decision to do all in his power to have the lake preserved as a national park, a purpose to which he devoted the next seventeen years of his life.

Upon his return to Portland he immediately petitioned President Cleveland to set aside ten townships from settlement. Since no survey of this portion of Oregon had been made, Mr. Steel guessed as to the area which would include the lake and then a portion of the surrounding territory. His petition was acted upon by presidential proclamation the area designated as Mr. Steel was reserved.

In 1886, again upon petition of Mr. Steel the Geological Survey sent a field party, under the direction of Capt. Dutton, to make a survey of the region and soundings of the lake. Mr. Mark Kerr, for whom Kerr Notch is named, was chief topographer of the party.

One evening after considerable progress had been made in the preparation of the map, Mr. Kerr called Mr. Steel to his tent. He had the unfinished map before him. He casually asked Mr. Steel “How did you decide what area was to be set aside for your park?” “I had to guess at it”, Steel answered. “We had not authentic maps.” “Well”, Kerr answered laughingly. “Do you want it this way?” and he showed Steel where the eastern boundary of the proposed park cut across what is now Dutton Cliff to near Cleatwood Cove, excluding the east one third of the lake.

Mr. Steel was considerably surprised and somewhat disturbed by this revelation. But Mr. Kerr dispelled his worries by assuring him that he would fix the boundaries himself.

The line was drawn to include Scott Peak on the east, the many cones and craters, the interesting canyons cut in tuff south of the lake and the Pumice Desert on the north and the slope of Mount Mazama to the west. The total area is 249 square miles.

|

Flowers, Where the Scene-shifter – Nature – Is Always Busy

By Lincoln Constance

The casual visitor to Crater Lake is quite apt to be disappointed when he fails to encounter the profusion of flowers which greet him at Rainier or Yosemite. The light soil of the windswept Rim has not yet put forth its full burden of vegetation, but even the intermittently stormy weather has not prevented the alpine meadows near by from producing a rainbow of color. This floral display is best exhibited in the Castle Crest Gardens, Copeland Meadows and Munson Valley, but let us visit the first, as the most representative and accessible.

On the open flat we encounter the Newberry’s Knotweed (Polygonum newberryi),conspicuous by its large oval leaves, jointed stem, and greenish flowers. The brilliant yellow of the Sulfur Flower (Eriogonum umbellatum), growing close to the ground, next attracts the eye. Among the rocks at the side of the trail the Western Anemone Windflower (Anemone occidentalis) rears it round, feathery fruits. Just before reaching the meadows, the Wild Bleeding-Heart or Dutchman’s Breeches (Bicuculla formosa) and the False Solomon’s seal (Vagnera amplexicaulis) cooperate to form a border of pink, white and green, and so enliven the trail.

The meadow itself is a giant’s paint-pot, with dabs of all hues lavishly scattered over it. At the upper end, the Blue Forget-me-not or Beggar’s Ticks (Lappula diffusa), the Mountain Valerian (Valeriana sitchensis), and the blue of various Lupines (Lupinus) dominate the scene. But as we continue, we note splashes of various shades of red, the scarlet and yellow of the Columbine (Aquilegia formosa),the gaudy crimson of the Indian Paintbrushes(Casstilleja), and the rose-pink of the Lewis’ Monkey-flower (Mimulus lewisii), which is just commencing to bloom. On the borders of the brook, itself, the pink spires of the peculiarly-shaped Elephants’ Heads or Butterfly-tongues (Pedicularis greenlandica) mingle with the white clusters of the Alpine Smartweed (Polygonum bistortoides), while the White Violet(Viola blanda) and Alpine Buttercup (Ranunculua sp.) stud the green carpet of grass and sedges.

Several shrubs stand out conspicuously from the herbaceous plant. These include the Mountain Ash (Sorbus sitchensis), distinguished by its masses of white flowers borne in flat-topped clusters from the Red berried Elder (Sambucus racemosa), which bears its snowy flowers in cones. The Pine Manzanita (Arcostaphylos nevadensis) forms a mat in dry places, and is often supplemented by the Blue Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum), and occasionally by the Matted Beard-tongue or Penstemon(Penstemon menziessi var. davidsonii).

Less conspicuous but attractive flowers are the blue Alpine Speedwell flowers, the Shooting-start (Dodecatheoum alpinum),and two species of orchids — the Slender Bog-orchid (Limnorchis stricta) and the Boreal Bog-orchid (Limnorchis dilatata). The large green leaves of the Green Hellebore (Veratrum viride), and the young shoots of the Monkshood (Aconitum columbianum) and the Ragweed (Senecio triangularis) make up an important element of the herbage, but as yet are contributing few flowers.

We cross the bridge and again emerge upon the plain, where we are greeted by the Alpine Puss-paws (Spraguea umbellata), the False Alpine Dandelion (Agoseris alpestris), the Water-leaf or Pygmy Phacelia (Phacelia heterophylla), the Newberry’s Knotweed, which form the main cover. Patches of yellow or orange are formed by the Alpine Owl’s Clover (Orthocarpus), and the yellow of the Sulfur Flower again makes it appearance.

Colorful as the meadows now are, they give promise of even greater beauty to be anticipated. Do not think you have “seen” the garden because you have followed the trail to its end once. At every return you will find it wearing a different aspect, for it is a changing pageant of color presenting a new blended mosaic as only nature can mix her color combinations.

More About Bugs

By Earl U. Homuth

In previous issues of Nature Notes appeared a series of articles dealing with the efforts toward control and eradication of the Mountain Pine Beetle (Dendroctonus monticolae,Hopk.) which had attacked and threatened to destroy the pine forests of Crater Lake National Park and the surrounding areas.

As mentioned in those articles, the beetle is destructive, due to the fact that the larvae feed upon the cambium or living layer of the tree, horizontally from chambers in which the eggs are laid by the adult.

The solar method of control consists of felling the infested trees, exposing them to the sun. A sun temperature of 85 degrees for a period of one hour serves to destroy the eggs, larvae, pupae and immature beetles in the tree. The trees are subsequently rolled half over, thus exposing all surfaces.

Control work for a season must be completed or terminated by July 1 since by that time adult beetles emerge from the trees and subsequent work would be useless. The work for this season covered the period from April 30 to June 30. Due to a mild winter and early spring, and with experience gained in previous years the work was more rapidly advanced.

The number of trees treated this year totaled 14,747 over an area of 16,500 acres. This gives an average of .893 trees per acre. In 1930 the average was 2.2 and in 1929 it was 4.4 trees per acre.

When figures, covering the work of the past three seasons, are studied, they prove enlightening.

In areas completely treated in 1929, the average decrease of infestation in 1930 was 74 percent. The average decrease in 1931, over 86.1 percent.

In units incompletely treated the infestation showed an increase, in one instance, of 59.5 percent in one year and in another instance 82.8 percent in one year.

Observations in areas not treated indicate that the increase may run from 50 to 200 percent.

It may be concluded from the complete figures on file that partial or incomplete treatment is useless and that treating in areas subject to reinfestation is also unsatisfactory. Only complete treatment of all affected areas in one season will produce the desired results.

It may also be concluded that although the work has not been a complete success, yet, had nothing been done, the pine forests of the southern part of the park would present the same appearance of a “ghost forest” as is found upon 33,000 acres in the northern portion.

It is also obvious that the present incomplete treating will eventually eliminate all pine stands by cutting.

In conclusion it may be mentioned that the solar method of control was developed in Crater Lake National Park and that progress and results indicate that the method is successful, provided the treatment of all infested areas is thorough and complete.

Protection for the Coyotes

By Frank Solinsky

Many campers, while gathered around their evening fires, have been thrilled and held spellbound by an eerie call. The uninitiated conjures images of an attack by ferocious beasts but to the woodsman it is the wild and beautiful bark of a coyote.

Recently five coyote pups were found in the woods about two miles below Government Camp, by two of the Beetle Control men. The men played with the pups, which were about a month old, for half an hour and then left them unharmed. The den was under a large log and in front of the den was a dead porcupine. The coyote has the enviable ability of being able to kill a porcupine without injury to himself.

Possibly it will be remarked that since the coyote is a pest, the pups should have been destroyed. Although such is the practice in some of the parks, the authorities here at Crater Lake feel that the coyote is an integral part of the woods and should be protected. In fact, the coyote almost balances his good with his bad, for although he kills grouse and other birds and small animals, he also preys on the destructive porcupines, gophers and rabbits.

Pacific Belt of Volcanic Activity

By W. Layton Stanton, Jr., Ranger Naturalist

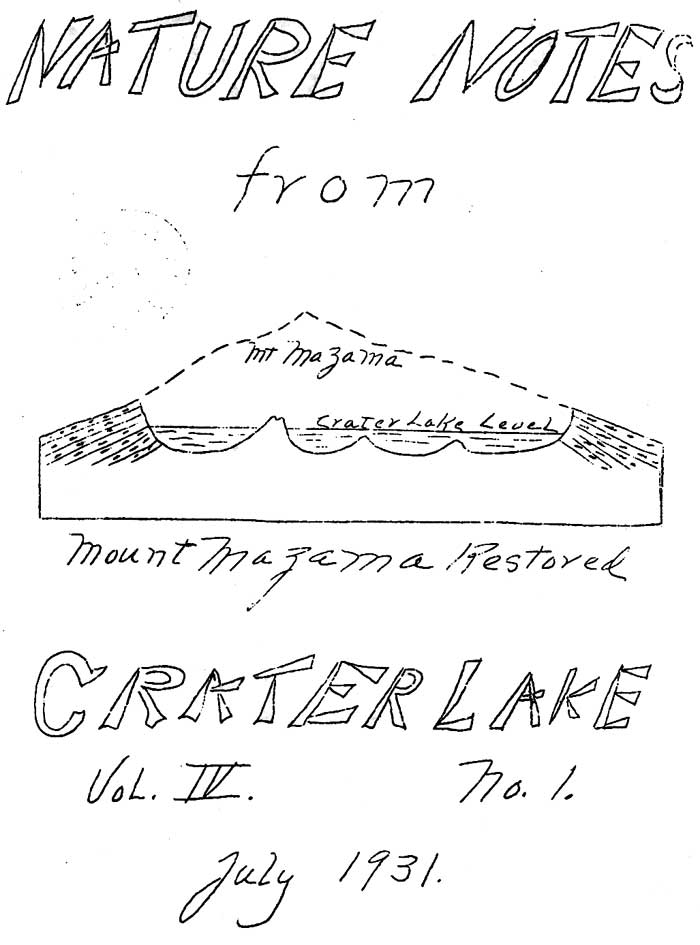

How many of us realize that Crater Lake lies in a belt of volcanic activity which entirely circles the Pacific Ocean? In the far north there are many evidences of volcanic eruption along the Aleutian peninsular of Alaska. This zone curves southward and extends along the western border of North America, South America and then westward across the southern Pacific Ocean. Many of the south sea islands, all of which owe their origin to volcanic eruptions, lie in this belt. The same conditions exist in the East Indies and along the eastern margin of Asia, thus completing the circle. Although the remnant of ancient Mount Mazama is but one of many thousands of volcanic peaks occurring in this zone, it is unique in that nowhere else is there found a lake, nestled in a crater or caldera, which can compare with our own Crater Lake.

Just what causes this great volcanic belt, science does not know. It must represent a zone of weakness in the crust of the earth through which molten rock and gases are able to reach the surface. But how may we explain the location of this relatively weak zone? That is another answered question. Some authorities believe that the weight of the ocean water pressing down on the ocean bottom forces subsurface material to either side, much as a block of wood might do if pressed down into a mass of heavy mud. This action might be expected to push up mountains along the continental margins and force molten rock and gas through the crust of the earth.

We should remember that Crater Lake and Mount Mazama, although magnificent and awesome in themselves, are expressions of some great system of forces which are continually at work in shaping our earth.

Other pages in this section