Volume 7 No.2 – August 1, 1934

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1934

The Trailside Speaks

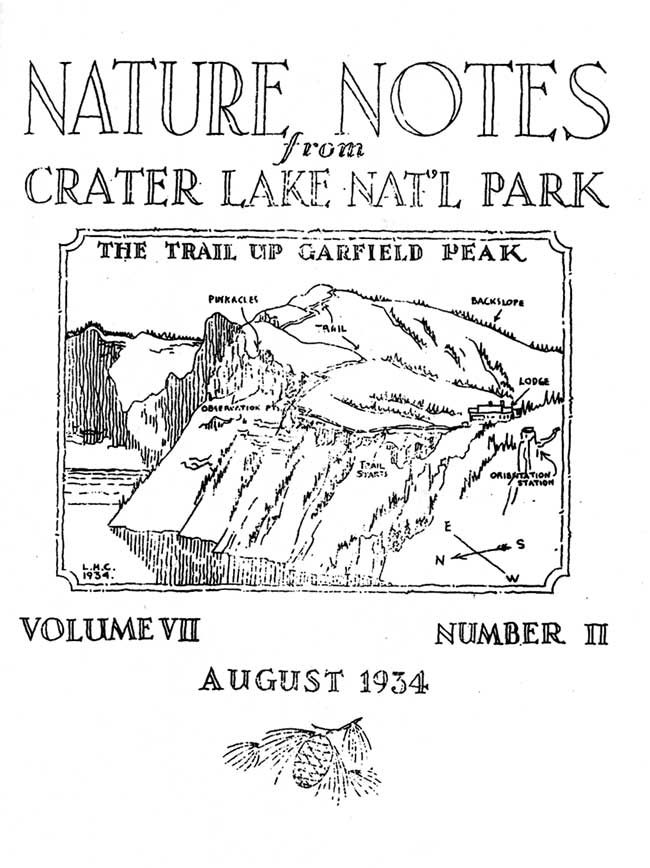

For those who have observant eyes and ears, the trailside speaks with many voices. Hundreds of stories of struggle and force are strewn along the ascent of Garfield. It is one thing to see the sign of the story; it is another to interpret it. On our way up the Peak this morning, let us look only for the signs of stories. As we begin the ascent, our eyes are drawn to a continuous spiral scar that encircles as a majestic hemlock from crown to base. The scar is fresh, exposing the lighter colored cambium layer. A story is here – a story of tremendous force and potential devastation, for lighting is one of the greatest foes of our forest areas. Crossing a barren ash slope further on, we find that it is dotted with Newberry’s knotweed and sulphur flowers. The botanist, could he uproot one of these plants, would illustrate by means of the root system an interesting tale of adaptation to arid conditions. Swinging up to the Rim again, our eyes are arrested by white bark pines stretching out over the brink in a horizontal position. Why are these plants not growing upright? The barren slope behind us and the exposed situation give us a hint to the story here, and a winter view of this spot would make it clear, for the combination of snow and wind has contributed to the position of these trees.

Moving along up the slope, we are startled by a sharp whistle close at hand. We look in vain for the source, and the dull browns and grays of the rock slide, tell us something of the marmot’s color, for surely nothing could be so close and yet invisible. We pass clusters of penstemon and potentilla side by side. A blur of motion hovers over the penstemon. We stop for a moment to observe that the potentilla holds no attraction for the humming bird. Why is this? The ornithologists could tell us the answer and it would be the story of the adaptation of plants to different means of pollenization.

Continuing upward, we pass an exposed ledge of rock whose material lies in well defined thin horizontal layers. To the ordinary observer it appears as a stack of huge plates, but the geologist knows that minerals and stresses entered into the formation of this curious mass. A few feet further on and we find ourselves with the placed Lake fourteen hundred feet below us.

Our eyes are drawn upward from the Lake along the profile of the tawny cliff that towers above us to the right. The whole scene has such an appearance of immobility that our eyes are caught by the slightest movement. Far out on the face of the cliff, standing on the top of a small upright pinnacle, a swaying pine tree attracts our attention. Miniature drama is represented in the situation, for we are observing the struggle between two forces: the forces of growth and the forces of destruction. Which will triumph? As we stand, wondering, from far below comes up to us the sound as of a snapping, crackling fire newly kindled, and we know that sound as audible proof that the forces of destruction are at work, for a rock slide is on its way to the Lake. We resume our walk, and from the rock wall that lines the side, the sun strikes back into our eyes from a small spot that shines like an opal. Here is an interesting story of the relationship between rocks and the weather, for without the winter’s snows melting far above this point, these spots would not have been formed.

Glancing upward we glimpse the summit and hurry on, eager for the view from the top. Our sleeves brush a tree that appears familiar but yet strange. Is it a pine? We examine the foliage. It is a hemlock and apparently mature, yet it is but a pigmy six foot brother to the majestic hemlocks that line the trail and the base of the peak. Why is it so small? The answer might be had from the botanist, who in answering would unfold the story of vegetation adaptation from the Arctic to Mexico.

At last we reach the top. To the south we can look into California and to the north we follow the profile line of the Cascade Summit, but our eyes return each time to the blue marvel at our feet, two thousand feet below us. We do not wish to think now. We wish only to gaze at this example of titanic force from the past, and comprehend, if we can, its present, living beauty.

The Geology of the Garfield Trail

By Carl R. Swartzlow, Ranger-Naturalist

The Garfield Trail speaks in many languages. The song of the birds and the rustle of the breezes through the hemlocks and pines are the first sounds to great the ear, and they follow one all the way. This language is also expressed in less musical tones. As one approaches the Rim and looks toward the Lake, a rumbling sound is heard and attracts the attention to boulders, loosened by erosion, tumbling to the narrow beach at the water’s edge. Jets of dust rise at points where the boulders strike on their downward journey. It is only after gazing at the inner Rim for several minutes that the grandeur of the scene unfolds and one realizes that the landscape of color dominates this trailside.

The Garfield Peak Trail may be called a study in brown. From the point where one first ascends the trail, thence to the top of the peak, one is constantly impressed by the ever changing shades of red, brown, and yellow. The causes for this particular series of colors are related to the most fundamental processes of geology an should be a part of the knowledge of every lover of the out of doors.

The reds and browns of the rocks along the trail are usually a result of the first stages of rock decay, and all subsequent compounds released are stained with these colors. The constituents of the pigments are oxygen, iron, and water. The iron oxides (iron united with oxygen) are a constituent of nearly every variety of igneous rock. Iron may not be a diagnostic element in some varieties of rock but its presence is all but universal. The abundance of iron oxide determines in a large measure the depth of color found in the weathered rock products.

Usually the iron in fresh rocks is not fully united with oxygen, i.e., oxidation is not complete and in this state the iron is soluble and is relatively colorless. Moisture that comes in contact with rocks has previously dissolved varying amounts of the atmospheric gases, of which oxygen is a common constituent. The oxygen in the water unites with the iron of the rocks and produces a compound in which the iron has taken on all the oxygen possibly and in this latter state is one of nature’s most insoluble compounds. If water as such has united with the iron oxide the resulting compound (the mineral limonite) has a brown color, and if the compound is diluted the resulting color is yellow. If no water has entered into the reaction, the color of the resulting rock is red – the mineral hematite. If the soluble and insoluble iron compounds are mixed a greenish color is produced. It can be seen readily that combinations of these colors in various stages of dilution can produce an infinite variety of shades that enhance the beauty of the trailside.

At the beginning of the Garfield Trail one walks over a mass of buff-to-tan pumice dust. Undecomposed fragments of this volcanic glass reflect the sunlight as if the pumice contained myriads of diamond chips. In time their lustre will be dulled by the chemical action of the atmosphere or by organic acids released by decaying vegetation. The pumice soils contribute little essential plant food, and only the more hardy grasses and flowers are found growing upon them. Where abundant vegetation appears to be growing in pumice, the plants are usually rooted in more fertile soils below.

A few yards beyond the point where the trail first touches the Rim, and at several other points along the trail, the lava rocks (mainly andesite agglomerate) have been decomposed and young soils have been formed. These soils have a chalky appearance in contrast to the usual yellow or brown soil along the trail. These formations are seldom a result of normal weathering processes, but are probably due to the action of heated waters that escaped along the slopes of Mt. Mazama. The rocks have been almost completely decomposed. The residual material is the mineral kaolin or some variety of it. (Kaolin is the chief mineral constituent of clay). If one moistens his fingers and rubs them over some of these particles, a greasy or doughy ball of clay is readily formed.

About halfway to the top of the Peak there are additional examples of rock weathering that are more common but are none the less interesting. Large masses of volcanic agglomerate have been weathered for long periods of time by normal processes. In the construction of the trail, cuts have been made through the rock mass, and cross sections of many boulders are left to tell the steps that nature has used to bring about the changes from solid rock to soil. The sub-angular fragments of rock have clear outlines, but they can be crushed easily with the fingers.

In many cases a series of concentric bands, similar to the peelings of an onion, surround a central portion of rock that is relatively undecomposed. The cause of the banding is a common process observed in moist climates. Moisture penetrates the pore spaces of the rock. The depth of penetration depends upon the size of the pores, temperature, and character of the solutions. When the optimum depth has been reached, the moisture tends to decompose the rock. The new products formed are of greater volume than the original rock minerals. Consequently, swelling occurs and the shell of altered rock, as thick as the depth of moisture penetration, cracks away from the original rock. After the first shell has been released there is a ready passage for the succeeding influxes of moisture to penetrate the rock below and the same process repeats itself. This type of rock decay is called spheroidal weathering. Upon prolonged exposure to the elements the banding disappears and a homogeneous mass of soil is found where the boulder was situated originally. In a few instances the bands may appear to be of different colors. This is probably due to the amount of iron oxide absorbed by the soil during the breakdown of the boulders.

The foregoing examples can be readily contrasted with the fresh unaltered rocks along the talus slopes and the rock cuts along the trail. One is impressed by the ceaseless effort of natural forces to break down the rocks on the earth’s surface. This is to provide soil and plant food so that the fauna and flora of the earth may carry on their life functions.

The names of several rocks have been mentioned above. The first, pumice, is present in varying amounts along most of the trail. Its most common mode of occurrence here is as a fine buff-colored material. In a few places fragments several cubic inches sin volume may be found.

These larger fragments exhibit all of the common characteristics of pumice; namely, light buff-to-tan color, glassy texture, and high porosity.

Pumice is invariably associated with explosive vulcanism and consequently the original magma is charged with gases, usually water vapor and carbon dioxide. The gases, under pressure, are forced into the viscous lava, thus producing the characteristic porous texture. The lava hardens before the pore spaces are eliminated.v

The next most abundant rock is andesite. It differs markedly from pumice, both in composition and the manner of its formation. Andesite, the common flow rock of Crater Lake, is rich in iron, magnesium, and calcium, and poor in silica. Pumice, on the other hand, has a high silica content with very minor amounts of the other elements. The pressure of the iron, magnesium, and calcium in the lavas increases their fluidity, thus permitting them to flow over wide areas. Common with most andesites, those of Crater Lake are porphyries. That is, there are large crystals embedded in a more dense background called the ground mass. The most common cause for the formation of porphyries is a change in the rate of cooling. When deep within the earth, the lava started to solidify or crystallize and numerous minerals (feldspars) grew to the size shown in the rocks. Then pressure from below forced the lava to the cool surface where rapid solidification stopped the mineral growth and caused the running lava to harden about the earlier formed minerals.

The only other rocks of importance is a volcanic agglomerate. This is a rock composed of fragments of the various igneous (lava) rocks of the region. During periods of explosive action all of the types of rock present were thrown into the air and then upon descent filled cracks and gullies in the sides of Mt. Mazama. Later, lava flows or percolating waters caused the fragments to be more or less consolidated. Two-thirds of the way up the trail an excellent view station is located where one can observe masses of boulders caught in the lavas. This shows that in some parts of Mt. Mazama, lava flows and explosive eruptions were simultaneous. Perhaps the boulders merely tumbled down the mountain side and were caught in the flow, or else were engulfed as the lava moved along.

Fragments of the mineral quartz may be seen among the talus debris along the trail. The mineral is a variety known as milky quartz and is common the world over. It has formed by solutions rich in silica rising through cracks in the sides of Mt. Mazama. The rarity of quartz as well as other secondary minerals is significant.

In several places along the Garfield Peak Trail are large white blotches on the rocks. This is especially true of the areas of volcanic agglomerate. These white spots represent areas where hot moist gases escaped to the surface of Mt. Mazama.

The rocks are largely kaolinized, but with the outline of the rock fragments retained. If the rocks are rubbed with the fingers the typical clayey feel can be readily recognized.

We and the Birds – Garfield Peak

By W. Craig Thomas, Ranger-Naturalist

This morning, let us take a stroll up Garfield Peak Already we can hear the songs of birds that have learned better than human beings how to sing at their work.

As we pass the Lodge, going along the rock wall, a wise-looking marmot surveys us with dignity appropriate to his station and slides off the other side of the wall. When we reach the place, however, he has vanished within the rocks. But a sudden sweet song allays what disappointment we may feel.

It is the tinkle bell song, the thrill of Thurber’s Junco. And then we see him, perched at the very tip of a small tree, sending his lovely thread of song into the surrounding forest. The female is busy gathering tiny insects and seeds in the dense grasses and plants at the foot of the tree. Her nest is carefully hidden under the leaves of the trailing currant, but if we watch we can find it. We notice, also, that her beak is heavy and thick, in order to crack the shells from seeds that she many find. But while we are watching her, we become conscious of another song, the metallic buzz of the Western Chipping Sparrow. And suddenly we see him, perched on the top of a stump in the little meadow. His locust-like song comes thinly across to us, and fearing to frighten him, we stay where we are. But through the glasses, we can see the chestnut patch on the top of his head, and the heavy beak that marks him as another seed-eater.

It is the tinkle bell song, the thrill of Thurber’s Junco. And then we see him, perched at the very tip of a small tree, sending his lovely thread of song into the surrounding forest. The female is busy gathering tiny insects and seeds in the dense grasses and plants at the foot of the tree. Her nest is carefully hidden under the leaves of the trailing currant, but if we watch we can find it. We notice, also, that her beak is heavy and thick, in order to crack the shells from seeds that she many find. But while we are watching her, we become conscious of another song, the metallic buzz of the Western Chipping Sparrow. And suddenly we see him, perched on the top of a stump in the little meadow. His locust-like song comes thinly across to us, and fearing to frighten him, we stay where we are. But through the glasses, we can see the chestnut patch on the top of his head, and the heavy beak that marks him as another seed-eater.

We are rudely interrupted in our bird watching by the raucous cries of some argumentative Clark’s Nutcrackers. In the top of a dead snag, they flaunt their family rows to the whole world which unfortunately is not very interested. And then we see the animated beauty and the dark grey of Allen’s chipmunk. We had seen already the smaller and brighter Klamath chipmunk scurrying near the rim as we started. The golden-mantled ground-squirrel we already also knew as the little beggar of the rocks, forever asking, however silently, for a hand-out.

Then as we go on past the meadow toward the rim and the broken colors of the rock slide, from trees along the path, we hear two songs so much alike that we must listen carefully to detect the difference. One we are sure is the purple finch, Cassin’s in this altitude, and soon we see him, his red head shining against the background of mountain hemlocks. His beak, too, is heavy, so we automatically place him with the junco and the chipping sparrow as a seed-eater. The other song we think comes from the Lincoln sparrow but he is too hard to find in our limited time so we go on up the trail.

But we do not proceed far, when the sudden flash and beauty of yellow and black tells us a Western Tanager has crossed our path on swift wings. As he perches for an instant on the dark green of a hemlock bough, we see clearly the red head, the yellow body, and the black wings and tail of the most beautiful of our western birds. We almost overlook the quiet green of his mate in our admiration of him. Then from the rockslide comes a strange little cry, the almost nasal whistling of the little cony.

Swiftly we focus the glasses; this little fellow seldom waits to be seen. But we have a brief look at his soft grey body and his little rounded ears. If his ears were long, we would know him for what he is, one of the rabbit family, but now we shall have to take the scientist’s word for it. The sudden mocking-bird song of the rockwren turns us toward the higher parts of the rockslide to see his ridiculously long bill and his sandy plumage. That bill of his can gather insects from strange crevices in the rocks. Then the low cry of the mountain bluebird makes us conscious of the female of the species. She is feeding her young ones on a dead snag where the nest is at the bottom of a hole, probably made by one of the woodpeckers. The male on the tip of the snag shows off his bright blue in the sunlight. And farther on the russet breast of a robin shows on the smooth ground under the trees. For a moment we walk through a grove of trees, where the staccato song of the Audubon Warbler comes to us from the higher branches of a tree. We get just a glimpse of the lovely lemon yellow of head and wing against the dark blue-grey of body, before he is gone. And we wonder why the warblers in such beautiful plumage so frequently hid their light under the bushel of a habitat in the very tops of the trees. And we watch vainly for a reappearance of our warbler, we see another lovely dweller in the tree tops, the tiny Golden-crowned Kinglet, and we can hear the faint “tsip, tsip” of his voice.

But suddenly the yankee of the bird world interrupts our search, and we successfully look for the red-breasted nuthatch, as he goes up and down and round the trunks and branches of trees, completely defying any sort of gravity there is. And near him, the slender-billed nuthatch utters his nasal ‘yank, yank’ along with his smaller brother. The chickadee, too, is here in this little grove, cheerfully telling the world who he is and, if you listen, what he is doing. He is not the least bit bashful, and is a relief after the charming but aggravating secrets of our warblers.

As we climb higher, and look back over the slope of the mountain, we can see the dead and bark-stripped tips of some of the smaller trees, sure evidence that the deliberate porcupine has been at work of nights. But our glance is caught by the smooth, soaring flight of a pair of red-tailed hawks as they float high above us. And it gives us a secret thrill and a little shiver to realize that their telescopic eyes can focus on us much more clearly than our glasses can focus on them. But as we move on, a sudden crashing of brush, where we have disturbed a black-tailed deer, startles us. Looking around, we become aware of a strange series of depressions making a sort of trail. We knew immediately that, although bears are not common on the rim itself, here is one of the trails, each bear stepping in the tracks of the one before it. Generations of bears may have made this trail.

We are nearing the top now, and our eyes see little but the magnificent view that we can see from the crest of Garfield Peak. But the constant twitter and sudden brilliant song of the rosy finch attract our attention, at least for a moment. Here is a bird that can truly be called a snow-bird, nesting almost beneath the melting snow banks and feeding on the frozen insects and scattered seeds on the snow banks themselves. Then comes the climax to a wonderful morning, as below us, so far that our glasses are again needed, but unmistakable in the wonder of flight and the contrast of brown and clean white, we watch the flight of the king of birds, the bald eagle. He strangely enough is fishing, and we see him swoop and strike the water. Soaring up from the white splash on the deep blue, he lands on a nearby snag. The eagle is eating lunch, and we being to feel that right now that is an excellent idea.

The Badger Game

By Russell P. Andrews, Ranger-Naturalist

On July 31, Ranger-Naturalist Moll, Waesche, and Andrews were riding over the Castle Creek motorway, with Boundary Springs as our destination. As our car rounded a curve, we surprised a badger in the middle of the road. He turned on us, teeth bared, and apparently determined to fight the automobile to a standstill. He did, for when the car was brought to a stop, three feet from him, he was still holding his position, determined to do or die. He was flattened out like a rug and to our startled eyes appeared a foot and a half broad. He did not retreat for perhaps a minute but when he decided to do so, it was in accord with the best military tactics. He would run a few feet, turn, and take a stand. This he would hold for perhaps half a minute. Then he would run and turn again, repeating this procedure until he was lost among the trees. We all agreed that when a badger fought an automobile, that was news.

The Ecology of the Garfield Peak Trail

By Berry Campbell, Ranger-Naturalist

There are two chapters in the story of Crater Lake: One, that relating to the geological history of the region – how the mountain was made; the other tells the story of the plant cover – how this originally bare region came to be clothed with vegetation. It is this second chapter which we shall here consider.

It is a fact which we may all observe that nearly any region which has a good soil will have a covering of vegetation. This vegetation, or plant community, is directly under the influence of the weather. The species which go to make up this plant community are dictated largely by the temperature and humidity. Alexander von Humboldt, many years ago, observed that as one climbed the high mountains of South America, the vegetable covering came more and more to resemble the polar forms. In other words, altitude and latitude acted similarly upon the forest covering – the prime factor being temperature. More recently this zonation has been painstakingly investigated on the high mountains in our own country. Not only does the plant community change with temperature differences, but as one goes from wet to dry climate, there will be a change from forest to prairie to desert, though the average temperature may remain about constant. From these observations, we may draw the conclusion that our final forest covering at Crater Lake is determined principally by the climate and that the soil, provided it is adequately rich and deep, is not great factor.

But there is a long and fascinating history to the soil and its formation from the bare lava flows of which Garfield Peak was originally composed. Trees will not grow on bed rock, nor will bushes nor grass. What then was the first vegetable covering?

Let us then examine the plant covering of Garfield Peak to see if we can unravel the history of the forest. As we stand on the switchbacks we note that where bare lava is exposed, there is only one plant to be found – the lichen. Here is the plant which is able to grow on the recent flows, and which preceded all other plants in this volcanic region. This small organism encrusts the cliffs around the Lake and is responsible for the green patches on Dutton Cliff and Sentinel Point. Its functions are several: it conserves soil by collecting dust in the same manner as does a carpet; it sends tiny rootlets down into the rock and hastens the breaking down of the stone; and it also enriches the soil by contributing its dead carcass to form humus or leaf mould.

But we will notice that where the soil formed by the lichens has collected into crevasses and depressions, the mosses have invaded. Because of their greater efficiency in wresting a living from the soil they are able to predominate over the lichens in all but the exposed places. The mosses, like the lichen collect, form, and enrich the soil. Because of their size, they carry on these processes at greater speed. And it is that which is their own undoing, for if we look carefully, we will see the lowly moss yield to the fern – its superior in height and complexity. The mosses remain only in the less favorable situations.

It is not until the cliffs give way to the steep talus slope that the ferns bow to the sedges and grasses. The more efficient seeding of the latter plants coupled with ability to endure dryer soil give them the upper hand on these slopes. The perennial flowering plants such as the various forms of wild buckwheat, arnica, bleeding heart, and Indian paint-brush may bee seen to grow in the grassy places and so they share this stage of succession. The inroads made by the shrubs into this plant community may well be seen near the foot of the peak in the region of the first switch-back, for there the Ocean Spray, Squaw Carpet, pine mat, and currant grows in profusion and apparently to detriment of the lower forms.

The final plant community, or the climax community as it may properly be called, is the forest. The first forest may be seen on the steep hillsides as a mixture of white bark pine and hemlock. Before optimum conditions were reached one or the other of these species is thinned out and we find that near the crest of the ridge the white barked pine exists in almost pure stands, while below it are unmixed hemlock forests.

What a complicated bit of machinery Nature puts into motion in order to build a forest! We are inclined to be impatient when we see that the first stages may well take hundreds of years. Let us not forget that years mean nothing in the workings of the universe, and that the human life is but the flicker of a candle compared to the life of old Mt. Mazama. We are also distressed that this machinery does not seem to be as precise as the polished automatons which run our ships or grind out shoes or automobiles. One thing does not follow another as the textbooks would have it. Many of the stages are overlapping or run together. A most excellent example of this is to be seen on the large rock the second switch-back from the summit. Here we may see lichen, or six varieties, in the greatest of profusion, while in the crevices the rest of the life history of the forest is written in complete form. Mosses, ferns, sedges, grasses, flowers, shrubs, pines, and hemlocks grow all within an area ten feet square. This rock stands as a summary of the second story of Crater Lake and refreshes the memory of the traveler on Garfield Peak.

Other pages in this section