John Lowry Dobson Oral History Interview

Interviewer: Owen Hoffman

Interview Location and Date: Peyton Room, Crater Lake Lodge, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, July 31, 2004

Transcription: Transcribed by Owen Hoffman, with editing from Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park historian, December 2005

Biographical Summary (Photo and bio. summary from Wikipedia.com)

John Lowry Dobson (born September 14, 1915) is a highly influential amateur astronomer. He is most well known in astronomy circles because his name is attached to the popular Dobsonian telescope design. He is credited for inventing the design, which is used by a large number of amateur astronomers. He is lesser known for his efforts to promote awareness of astronomy through sidewalk astronomy. Dobson’s popularity, particularly his association with telescope building, has made him a frequent guest at meetings of amateur astronomers. He often leverages this popularity to draw attention to his unorthodox views of cosmology.

John Dobson has been dubbed by some as the “pied piper of astronomy”, and the “star monk”. He was the only amateur astronomer highlighted in the PBS series The Astronomers, and appeared twice on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. He has also been featured in two recent documentaries, Universe–The Cosmology Quest and A Sidewalk Astronomer.

He was born in Beijing, China. His maternal grandfather founded Peking University, his mother was a musician, and his father taught zoology at the University. He and his parents moved to San Francisco, California in 1927. His father accepted a teaching position at Lowell High School and taught there until the 1950s. He spent 23 years in a monastery, after which he became more active in promoting astronomy, and his own brand of nonstandard cosmology.

Materials Associated with this interview on file at the Dick Brown library at Crater Lake National Park’s Steel Visitor Center: taped interview

In this 1994 video John Dobson reviews his life of sidewalk astronomy and makes the case for amateurs going public with their scopes. Includes clips from his telescope making and cosmology classes.

To the reader:

During the Leonid meteor showers of November 2001 my wife and I camped about 5,000 feet, on top of Hooper’s Bald in the Cherokee National Forest of North Carolina. The wonders of the night sky that evening changed something within me. I knew I had to begin to learn more about the stars and galaxies above.

I began by reading beginners guides to the stars and planets and purchased my first astronomical binoculars. By February 2002, I bought my first telescope, an eight inch Dobsonian. The very next week, I had had the good fortune of traveling on business to Los Angeles. Having some free time, I decided to visit a famous telescope store in Woodland Hills. There, I ran into Bob Alborjian, a member of the Los Angeles Sidewalk Astronomers. He had overheard that I just purchased a Dobsonian telescope and asked if I would like to meet John Dobson himself. I was told to come to Griffith Park Observatory that evening. When I arrived, I saw John Dobson with a ten inch Dobsonian called “Tumbleweed” inviting all within earshot to have a look at the moon and the planets. He was even talking to the Japanese in their language! I was instantaneously convinced of the merits of sidewalk astronomy as practiced by John Dobson.

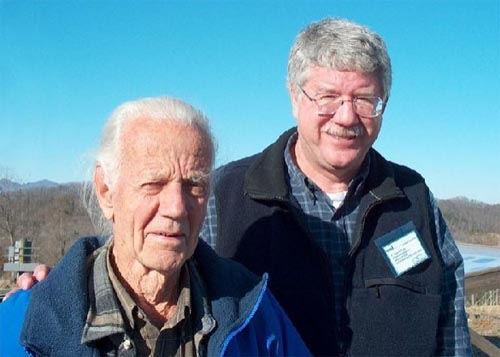

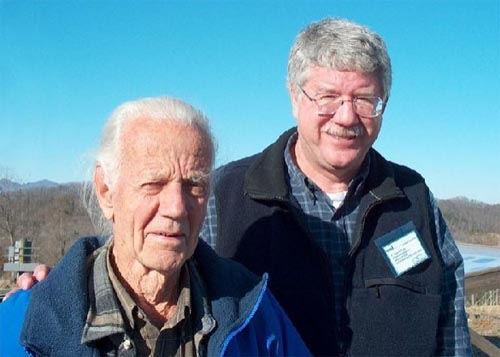

John Dobson and Owen Hoffman (interviewer)

I asked him if he had ever considered taking sidewalk astronomy to the national parks. He laughed, and said, “Of course! National parks are the only places where the seeing is good enough and the public numerous and curious enough to allow us to show off the wonders of the night sky using large telescopes like our home made twenty-four incher.” I asked whether or not he had been to Yosemite, and he said, “That was one of the very first parks visited by the Sidewalk Astronomers.” I asked him had he been to Crater Lake, and he said, “oh yes, several times.”

I told him that I was a former ranger-naturalist at Crater Lake and he immediately began to tell me of the kind hospitality offered to him by naturalists Hank Tanski and John Salinas. He also said he knew of park interpreter and planetarium director Tom McDonough. He said he had stopped coming to Crater Lake since the closing of the Rim Center (the Community House) in 1988. He said that he believes it to be absolutely necessary to give slide presentations prior to the use of telescopes, so that people looking through the telescopes would have some appreciation of what they were observing. The closing of the Rim Center made it impossible to give such presentations.

Knowing that 2002 would be the year of the park’s centennial celebration, I immediately sent out e-mail to all I knew who remembered John Dobson’s park visits. I suggested to Superintendent Chuck Lundy that a star party at Crater Lake be organized as a part of the park centennial celebration and that Dobson be park of this event. As it turned out, this was not to be. The park had other priorities that summer, and night sky interpretation was not among the specific activities planned for the park’s centennial. Not to give up on a good idea, I proceeded in the following seasons to promote the possibility of bringing John Dobson back to Crater Lake and promoting the value of dark skies above national parks as both a natural and cultural resource.

On July 30-31, 2004, John Dobson returned to Crater Lake as a guest of the Crater Lake Institute to receive the Institute’s annual award for excellence in public service “for inspiring dreams about places beyond Earth through pioneering sidewalk astronomy in our national parks and forests, where curiosity and dark skies meet.” As a part of this event, the Crater Lake Institute sponsored public presentations by Dobson at Pioneer Hall in Ashland (July 29), the county museum in Fort Klamath (July 30) , and at Diamond Lake Resort on the Umpqua National Forest (July 31). No presentations, however, were given within the park proper.

The following interview with John Dobson was conducted on July 31, 2004 in the Peyton Room at Crater Lake Lodge. I as interview functioned as a Volunteer-in-the-Parks.

December 2004

Can you give us some background about yourself.

I was born on Sept. 14, 1915, in Peking, China. My mother was born there as well. Her father was the founder of Peking University. We came to this country in 1927 because of political unrest and settled in San Francisco. Since moving from China to the USA, I have mostly lived in San Francisco except for a nine year period when I lived in the Vedanta monastery in Sacramento. Nowadays I live all over the place.

In Peking, (Bejing), my brother and I attended the American school. But my parents were not pleased with what was being taught there, so they opened a school at home. They were both teachers and provided me with a thorough educational foundation. I attended grade school in San Francisco, and then went to Lowell High School, a college preparatory school where my father taught biology and zoology. In 1934 I attended the University of California at Berkeley and majored in chemistry. In those days we paid only $54 a year for tuition, but this included two years of mandatory ROTC military training. I first went to the university to study biochemistry with the avowed purpose to keep Einstein alive, so he could continue to figure this whole bloody thing out. Ever since I was a child in Peking I was terribly interested by Einstein and gravity, so I could study the cosmos. But I didn’t go straight through the university: after about two years at Berkeley, I became fed up, so I quite school. After a couple of more years I went back, but I quit again after just one semester. I didn’t graduate until 1943.

Of course, I never succeeded in keeping Einstein alive. I also didn’t realize that I was going to inherit his problem [of figuring out the origin of the cosmos]. There are some things that Einstein did in 1905 that were terribly important. I think he took his physics seriously, but not geometry. I also believe that he probably never saw that his writings were being misinterpreted by those teaching relativity at that time. According to Einstein, E=m. The c squared is just how many ergs are contained within a gram of matter. But Einstein’s equation was being taught all over the planet as E + m= k. Einstein never made that mistake, but he apparently never saw how it was being taught. Someone in Hollywood once asked me, why didn’t Einstein clear this up? After all, he was around until 1955. But he probably never saw how it was being taught. Who would have had the gall to teach the subject of relatively in front of Einstein?

At the time I graduated from the university in 1943 we had to choose between a war-related job or rifle [active duty in the military]. Things were tough, the only holidays we had off was Christmas Day. We got Easter off, but that always fell on a Sunday, and we always got Sunday off. I had to do war-related work at the Rad Lab at Berkeley for about a year and a half, and then in 1944, the Swami allowed me to join the monastery. But I had to get out of the Manhattan Project through a double interview with the FBI. The second man asked me, “Do you think that the best thing you can do for your country at the present time is to join a monastery?” “Yes,” I said. He replied, “You might be surprised, buy many people feel like that.” I was surprised and wondered: How does he know?

So joining the monastery had nothing to do the with the war work you doing at the time?

Not particularly. I was a belligerent atheist when I first heard Swami Ashokanandra speak in February 1937. But when that man opened his mouth, I knew I had made a mistake. I had prematurely presumed that the notion of God was a mythological thing. But in listening to Swami, I knew instantly that I had made a mistake. By 1940, I knew I wanted to join the monastery. I went to Swami for instruction, and he sent me back to the university.

By the time I entered the Vedanta monastery in 1944, I knew that the universe was primarily made of hydrogen and that the principal energy in the universe was gravitational collapse. Gravity was the force that caused the hydrogen to fall together and that’s what made the stars and galaxies, but I wanted to make a telescope to watch it happen.

You had an interest in astronomy before you had a telescope?

As a child my father had one of those stupid refractors. It was without a mount, so we simply leaned it against something to view through it. I remember when I was in grade school making drawings of Jupiter its moons on different nights. These pictures were made on dark blue paper, two feet tall and a foot and one-half wide. They were really big pictures.

When did you decide to make your first telescope?

While I was in the monastery in San Francisco, I became intensely [interested] in actually seeing what was out there. I wanted to see it happening. My friend said that I could grind my own glass, and I said, “You’re nuts.” I can’t remember the exact dates when we did this, but it was quite a few years after entering the monastery in 1944.

We began making our first telescope using twelve inch porthole glass. We ground it against another 12 inch porthole glass that we found in a salvage shop at the foot of Filbert Street in San Francisco. The grinding of the glass required the use of carborundum which could be purchased readily in San Francisco.

When I first saw the third quarter moon through this twelve inch telescope, I thought, “My God, it looks like I’m coming in for a landing.” And I thought, “Lordy, Lordy, everyone has got to see this!” And that is when the idea of public service sidewalk astronomy got into my head. This was about 1956 or 1957. I went to the Vedanta monastery in Sacramento in 1958. The idea that others should have the opportunity to see what I could through my telescope is the reason that as soon as I was expelled from the monastery in 1967, we immediately began work to organize the Sidewalk Astronomers in 1968.

Could you tell us something about the Sidewalk Astronomers?

We are a public service organization. What we do is get telescopes out for other people. We almost never set up a telescope to look through it ourselves, but when we run the telescopes for the public, we get to see what’s up there. We usually locate objects in the night sky without aid of a guide scope (finder scope), just sighting the object off of the rocker box and pull the tube around. But for the 24-incher, we have a guide scope. Even then, I would simple climb the ladder and pull the telescope around. I didn’t need a guide scope to find things since I knew where they were.

We had a small German refractor that we used as a guide scope at first, but it got stolen. I once managed to talk a military surplus store into donation a small 90 degree elbow telescope (amici prism) so that I could use this image device as a guide scope on the 24-incher. I remember asking the store clerk, who seemed very perplexed that I would request something that was to be sold. I looked past him, though, and addressed his boss. The boss told his clerk to “take John Dobson into the back room and let him have his choice!” The clerk could not make such a decision by himself, but had to get approval from his boss. That’s just the way things work, you know. By the way, in World War II, the amici prisms used for elbow telescopes were made by amateurs. The professionals couldn’t do the job.

Have you had formal training in astronomy?

No, I have had a formal course in astronomy. My knowledge of astronomy comes through personal study, along with basic training in chemistry and physics. An innate sense of curiosity also helps. However, when it comes to making telescopes from junk, I think I can hold my own.

When did you get the idea to take your telescopes to the national parks?

In 1969, we were invited to go to Riverside, California, to attend an amateur telescope making conference. Sidewalk Astronomers seldom ever go out of their way to attend such conferences. My friend, Brian Rhodes, got the brilliant idea to go to Mexico to see the eclipse of the sun, even though we knew we could never afford to pay for such a trip. We decided that we would travel south to Mexico via Riverside, but only if we could do public service sidewalk astronomy while traveling to the conference. And that become our mode of operation. We only attend amateur astronomy and telescope conferences if we do public service activities along the way. Usually we stop by national parks and monuments to do this.

What was your first visit to a park?

It must have been Death Valley National Monument because the mirror of the 24-incher was not yet aluminized, it was only silvered. And the man who slivered it wrecked the edge, so I was to read the curve for refiguring and I hadn’t got it done until the last day because we came into Death Valley through a blizzard which tied up several thousand motorists in the passes. We needed to take it to a dark sky location to see what the telescope could do. It was in 1971 and we went out every two weeks which coincided with the opposition of Mars. Because we went out every two weeks, we could see the entire surface of the red plant.

Getting the 24-incher completed was all due to the tenacity and commitment of Brain Rhodes. I think we took it first to Glacier Point [in Yosemite National Park].

We typically would stay for two weeks at the park, and make sure someone was with the telescope during the day. We were most concerned that no one turned these telescopes into the sun. That was one of the big problems with a telescope left out during the daylight hours in the parks. One time in Death Valley we witnessed parents allowing their children to play inside the telescopes. One time at Glacier Pt. we saw children playing inside the telescopes and climbing on them. Sometimes they would throw things into them.

At Zion and Yosemite national park we received a stipendium from their natural history associations and were treated as official Volunteers-in-the-Parks. I think we have visited a total of about twelve national parks and monuments. We are still active each winter at Death Valley because Bill Clarke there made us unpaid employees, which allowed the group to be covered for insurance purposes and we could camp without being charged fees.

Was there anyone in particular who recognized the potential of the Sidewalk Astronomers as park partners and park volunteers?

At Crater Lake one of the naturalists, Hank Tanski, made us Volunteers-in-Parks and got us a food allowance. When the treasurer of the natural history association at Zion heard that more than three thousand people had used our equipment in six days and nights, he wrote us a check for $500. Dave Karraker in Yosemite really understood how things should be done. He saw the value of the Sidewalk Astronomers and wanted to have us give our slide shows in an amphitheater that would eventually replace the location of the portable toilets at Glacier Point. He envisioned that we would have several telescopes arranged along pathway where the old Glacier Point Hotel had been, and have people walk from telescope to telescope. A Sidewalk Astronomer volunteer would be at each telescope to make fine adjustments and tell the viewer what they were seeing. Sadly, Dave Karraker left Yosemite and this idea never was truly realized. He once said that if the National Park Service were to have a formal night sky program, the Park Service would have to purchase the telescopes, house them, and then have to hire someone to maintain the telescopes. But with the Sidewalk Astronomers, they could tour more than just one national park for only $5,000 a season.

You also visited the Grand Canyon, didn’t you?

The reason we went to the Grand Canyon is because Bill Clarke was transferred there, and he informed us of his transfer. He told us to come and we did from about 1978 through 1981. We used sun telescopes by day our larger telescopes by night, usually staying there 16 days and 16 nights. In 1980 we were asked to estimate how many people looked through our telescopes. We estimated about 20,000 people, but we had many telescopes with us at that time.

One time, after most people had gone to bed, a group of Australian astronomers stayed out past midnight at the Grand Canyon and spent the whole rest of the night sketching galaxies at our telescopes because many of the galaxies visible in the Northern Hemisphere are not accessible for night viewing below the equator.

In 1981, we received a letter from a park visitor who complained to the Park Service that we were raising controversial scientific questions with an uninformed public. A ranger at the Grand Canyon copied this letter and sent it to us, with a letter of his own asking us not to return. I’ve never returned on my own to the Grand Canyon. Others, however, have taken me back.

Can you elaborate on this letter you received in 1981?

It’s not nice that things happen like this. People who enjoy looking through telescopes don’t write letters. It’s only those who complain who write the letters. The complaints often come from the fundamentalists and creationists. They do not agree with our teachings. I think the ranger who sent us this letter may have been sympathetic to their points of view, or had even been one of them.

There are some other comments I would like to make as well about our experiences at the Grand Canyon, beginning with Dean Kettleson, who has organized an annual star party at the Grand Canyon and who recognized me as the initial founder of star parities there. He has invited me back several times (1). But the present Grand Canyon Star Party, unlike our sixteen day event, is only held for one week. I’d like to get the Grand Canyon Star Party extended to two weeks. One weeks without the moon and one week with it. When I first came to the Grand Canyon Star Party, I thought that it was a real shame that we didn’t bring our 24-inch telescope, but then I realized that we didn’t really need it. Why, there are a whole flock of telescopes out there for this event.

One another subject, I didn’t like the fact that the exhibits at the Yavapai Museum have been remodeled and apparently “dumbed-down” for public consumption. The original exhibits were among the best I’ve ever seen. I especially enjoyed the original exhibit that showed the ages of the rock strata in the canyon and the evolution of life with time. All of these very fine exhibits have been removed. Also, it upsets me that we can no longer show slide shows in the building itself. All of the slide shows are now out of doors in the wind. That is not so good.

Can you say something about your experiences at Crater Lake?

I can’t recall all the times we visited Crater Lake. It was many times. I don’t think it was annually, but certainly many times during the course of the year. I remember one time we came to Crater Lake from Glacier Point. The tubes had been drenched from a heavy rainstorm. They were too heavy for use. But Hank Tanski and John Salinas got us all sorts of heavy weight materials, about forty pounds of steel that we could us to rebalance the tube so that the telescopes could be brought back to use as the Rim. They put traffic cones on the parking areas to reserve the spaces for our telescopes and we could give slide presentations in the Community House after the formal talks given by park naturalists. It was very important for us to do these slide programs, because it allowed us to talk to the public about what it is they are about to see. I believe that it is essential to have a slide program that introduces the public as to what they are about to see through the telescope, before actually allowing them to look through the eyepiece. [JD refers to this as “flushing them down the tubes.”]

I am forever grateful for the assistance at Crater Lake. Hank would even let me stay in his home at Park Headquarters and let us take showers. He arranged for subsidizing our meals ($7.00 if we ate on our and $12.00 if we ate in the restaurant). It was just marvelous. It was wonderful when Hank Tanski was there. I don’t recall whether or not we were made official volunteers in the parks, however.

Over how many summer did the Sidewalk Astronomers visit Crater Lake?

I can’t recall, but certainly it was many summers in a row. We would stay for about sixteen days and have several assistants, but far fewer than our maximum number of about eight Sidewalk Astronomers. Unfortunately, we have no written account of our activities at Crater Lake and no photographs. We never used cameras. I’ve never owned a camera. I think our first visit was in the late 1970s and our last was in the 1990s. I enjoyed giving public slide programs at the Community House at Rim Village and then to talk to those who were curious enough to stay our after dark and climb the ladder to the eyepiece of the telescope.

We would put people in lines and tell them that if they wanted to see more after reaching the eyepiece, to get back in line. One time a lady came to us, climbed the twelve foot ladder to the eyepiece and said, “I’ve seen them dumb stars” and it was the ranger! [laughter]. We usually start with Saturn, and then after awhile the mothers with little kids go to bed. Then we show some of the clusters and galaxies for those wanting to see more and stay out later.

One year we had been in the park for some time. I noticed that the back of my van was filled with new supplies of food. I had no idea where this food came from, so I inquired around. I asked the ladies who worked at the Lodge. It turns out they were the girlfriends of the boys who worked on the boats. It was the boat crew who went out and purchased for us a totally fresh supply of food. They had been to the grocery store and bought sandwiches, fruit, and all sorts of delicious stuff. They had put all of that food in the back of my van. It was wonderful. God bless them .

We used to do the boat trip and while down on the lake, used our hands to scrape up the pollen floating on the surface of the lake and then consume it. It was very good food, but no delicacy. It’s the biggest pollen source that I’ve ever seen. I remember coming to Crater Lake in early July and having thirty foot snow banks. We would put our milk in the snow banks. I’ve been at Crater Lake over the fourth of July more than once.

One time at Crater Lake, we had our telescopes set up at the Rim Village area. A man came up to me and said, “These look like Dobsonians.” I said, “Yes, and I’m Dobson.” The man replied as he shook my hand, “It’s not often you get to shake hands with a Newton!” [laughter]

When was your last visit to Crater Lake?

It wasn’t long ago, perhaps seven years or so. It wasn’t as good as when Hank Tanski was here. There was no place to give a slide show. The Community House was closed (2). There were no facilities available to us for showers, so we were unable to shower for five days. The rangers weren’t interested in even looking through our 36-incher that we had transported to the park. I don’t remember whether or not we did the boat tours or not.

Is this present trip the only time you have visited Crater Lake without a telescope?

Yes, I’ve never come to Crater Lake before without a telescope. If feels strange not to have one. I feel like a tourist, especially with this room at the Lodge. I used to sleep in my van or in my 24-incher. We’ve had as many as three people sleep in that, you know.

When we would visit, one person stayed with a sun telescope and guarded our other telescopes. A sign was placed on our other telescopes that read “for night use only.” We would point them at the North Star since we know where the North Star is, even by daylight. Then the rest of us could tour the park by day. This allows us to become familiar with the park by day, and thus allows us to relate our introductions of the night sky to the features of the park as seen by the public during the daytime.

Can you share other experiences you’ve had in the parks?

We tried to do sidewalk astronomy in the Grand Tetons and in Yellowstone, but they could not make the arrangements for us. We had been to Bryce Canyon, Zion, Death Valley, Grand Canyon, Craters of the Moon, Rocky Mountain, and many other places. We still are active at Death Valley and in Yosemite, at Glacier Point. The rangers sometimes don’t always understand what we are about. One time at Glacier Point a security ranger told us that our telescopes would have to by put away by night! [laughter]. Another time we were told that the sky was not part of the park. I countered, “but the park is part of the sky!” A twelve year-old once complimented our activities by saying, “The programs conducted by the Sidewalk Astronomers are the only programs in the national park not geared for children under the age of nine years!”

I feel that it is very important that the night sky above national parks be treated as a important resource and that people who visit the parks be encouraged to stay out after dark. With telescopes it’s possible for them to see things they can’t view under city lights. After all, at night we are introducing them to the other half of the park.

We were once asked, “What is the difference between the Sidewalk Astronomers and the national park ranger?” My answer is, “The Sidewalk Astronomer entertains the public using telescopes in the park, while the park ranger entertains the public with the rest of the park.” We have been told by so many people who travel to many parks during their vacation that “Finding the Sidewalk Astronomers in the national parks has been the highlight of our summer tour.” Others have said, “It’s not just the telescopes, its also the slide show you give in the evening.” Still other say, “It’s not even the slides show, but the talks you give on relativity and quantum mechanics”

Is there anything specific you would like to say about Crater Lake National Park in particular?

Yes, I would. Crater Lake is to the Cascade Range what Saturn is to the Solar System.

Foot notes:

- The Grand Canyon star party attracts amateur astronomers from all over the globe.

- This was between 1989 and 2002. Tanski went to John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in 1988 and retired in 1996.

Other pages in this section

- Crater Lake Centennial Celebration oral histories

- Hartzog – Complete Interview (PDF)

- Jon Jarvis

- Albert Hackert and Otto Heckert

- Hazel Frost

- James Kezer

- F. Owen Hoffman

- Douglas Larson

- Carroll Howe

- Wayne R. Howe

- Francis G. Lange

- Lawrence Merriam C.

- Marvin Nelson

- Doug and Sadie Roach

- James S. Rouse

- John Salinas

- Larry Smith

- Earl Wall

- Donald M. Spalding

- Wendell Wood

- O. W. Pete Foiles

- Bruce W. Black

- Emmett Blanchfield

- Ted Arthur

- Robert Benton

- Howard Arant

- John Eliot Allen

- Obituary Kirk Horn, 1939-2019

- Mabel Hedgpeth

- Crater Lake Centennial Celebration oral histories

- Hartzog – Complete Interview (PDF)

- Jon Jarvis

- Albert Hackert and Otto Heckert

- Hazel Frost

- James Kezer

- F. Owen Hoffman

- Douglas Larson

- Carroll Howe

- Wayne R. Howe

- Francis G. Lange

- Lawrence Merriam C.

- Marvin Nelson

- Doug and Sadie Roach

- James S. Rouse

- John Salinas

- Larry Smith

- Earl Wall

- Donald M. Spalding

- Wendell Wood

- O. W. Pete Foiles

- Bruce W. Black

- Emmett Blanchfield

- Ted Arthur

- Robert Benton

- Howard Arant

- John Eliot Allen

- Obituary Kirk Horn, 1939-2019

- Mabel Hedgpeth