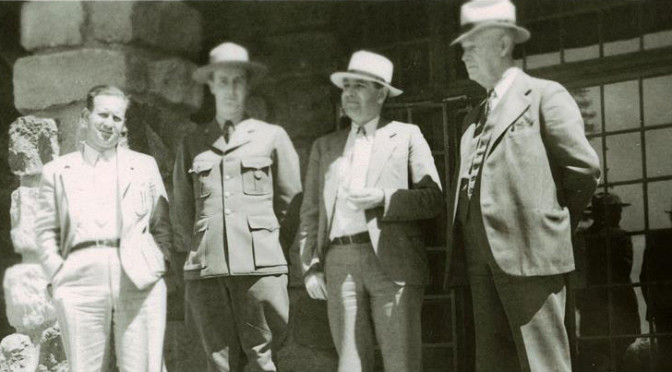

Photo above: (l-to-r)-Conrad Wirth David Canfield Lawrence Merriam Sam Boardman 1936

Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr. Oral History Interview

Interviewer and Date: Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park Historian

Interview Location: Corvallis, Oregon, November 25-26, 1988

Transcription: Transcribed by Amelia Bruno, 1994

Biographical Summary (from the interview introduction)

Lawrence C. Merriam is an emeritus professor of forestry at the University of Minnesota, though he continues to teach at Oregon State University on a courtesy appointment. He never worked at Crater Lake, but his father served as regional director in San Francisco from 1950-1963. His grandfather, John C. Merriam, has probably exercised the single greatest influence on the formation of the park’s educational program.

This interview took place in Corvallis represents the first of many visits with Dr. Merriam. One of the themes emphasized on the following pages was his work with the state of parks in Oregon. He has since published Oregon’s Highway Park System 1921-1989: An Administrative History and we have collaborated on other work involving wilderness, his grandfather, and the John Day Fossil Beds.

Materials Associated with this interview on file at the Dick Brown library at Crater Lake National Park’s Steel Visitor Center

Taped interview 11125-26/88. Notes from other conversations, all at his residence: 911 8/89, 1/19/90,2/9/90, and 411319 1. File includes copies of published articles, correspondence, and copy of Herb Evison’s (NPS) interview with his father. Several donations pertaining to his father and grandfather made to CRLA and other NPS units. Slide taken at the time of the taped interview. Copies of his administrative history of Oregon State Parks are in the park library.

To the reader:

Lawrence C. Merriam is an emeritus professor of forestry at the University of Minnesota, though he continues to teach at Oregon State University on a courtesy appointment. He never worked at Crater Lake, but his father served as regional director in San Francisco from 1950-1963. His grandfather, John C. Merriam, has probably exercised the single greatest influence on the formation of the park’s educational program.

This interview took place in Corvallis represents the first of many visits with Dr. Merriam. One of the themes emphasized on the following pages was his work with the state of parks in Oregon. He has since published Oregon’s Highway Park System 1921-1989: An Administrative History and we have collaborated on other work involving wilderness, his grandfather, and the John Day Fossil Beds.

Stephen R. Mark

(Crater Lake National Park Historian)

May 1995

We’ll begin with some general questions. Where did you grow up and what is your educational background. How did your father and grandfather influence that education?

I was born here in Oregon. My family moved to California when I was young. I went all the way through to my bachelor’s degree in the California school system getting my degree, a Bachelor of Science in forestry at Berkeley in 1948. Then I came to Oregon and worked with the state parks for a while. I did my masters and Ph.D. work at Oregon State, finishing in 1963.

My father and my grandfather were very influential in my education for a number of reasons. One was, of course, that when I was young I used to go around with them a bit and see some of the places that they were interested in such as the redwoods. We lived in Yosemite during the 1930’s. There I got very interested in the parks, not just the fishing and so on, but developed an interest in how they were created and managed. My grandfather was with us in 1940 and spent time with me. We talked about the relationship of Yosemite to the larger picture of National Park. He was very much interested in the protection of nature and is probably best known for working in the redwoods. He suggested that keep a journal. I didn’t do that partly because I was just a young kid. A little later, I went off to serve in the Second World War. It wasn’t until many years later that I began to realize the importance of keeping a record of the kinds of things that I was doing every day as grandfather suggested. I still do that.

My early work with the Oregon state parks was not as successful as it might have been because I got crosswise of the boss over protection of some of the parks. You can’t have a differing view with the people you are working for and at the same time be in charge of their planning. That was one of the things that I stressed in my subsequent academic work which I guess leads into the next questions about getting a job with the parks.

I worked here in Oregon as a salesman, then as a mill worker, over at Sweet Home for what is now know as Willamette Industries. In 1950, I was in Salem and talked with Sam Boardman, then head of the state parks, about the possibility of a job with them. He was just retiring at the time, but suggested me to his successor, Chet Armstrong. I landed a job with them as their information writer which ties into this business about Bill Langille, in that I took over the job that Langille had previously (1). Langille was quite an old man then and I talked with him a little bit about writing histories on the state parks. We had some differences about how to do it, I guess, so I didn’t see as much of him as I might have. I worked with the state parks, going from being information writer to being their park planner. We were just then developing overnight camping at the time and really expanding the state park system when I started in 1951. Sam Boardman, who had been the previous state parks superintendent until 1950, opposed camping. Governor McKay, however, said that the parks would have overnight camping. My job involved figuring out which parks needed to have a camp in them.

So McKay was development-oriented?

Yes. He subsequently became Secretary of the Interior in 1953. Of course, I think the big thing there was to get people to spend the night in Oregon. The argument was that they would drive from California to Washington without stopping because they couldn’t here. We had some wonderful areas that we could develop, so we did. About 1953 I got into a series of differences with Armstrong, who was parks superintendent. This was particularly acute over the development at Oswald West State Park, and then called Short Sand Beach, about whether to put a road down at the beach. Actually it centered on a latrine that’s now covered by trees. As a result, I was told that either you go along with us, or we’ll get somebody else.

I had already been thinking about doing graduate work so that I could teach. My interests centered on forest recreation. So I stayed with the state, working as the forester for the Highway Commission until 1959. That meant that I worked with the parks on blow downs and this kind of thing. I also worked on the freeway system, on what is now I-5 and I-84. This was when they were relocating these routes and buying property that was forested. I would appraise the timber. There were a lot of blow downs and we had salvage sales. I stayed with that until going to the University of Montana as an assistant professor of forestry, having done graduate work at Oregon State on a night school basis. From Missoula I went to the University of Minnesota as professor of forestry in 1966. I again headed up a program in outdoor recreation, called recreation resource management. I stayed with that until I retired in 1986.

Did you have any contact with the NPS during your time with the state parks?

Yes. We worked with the National Park Service, especially Neil Butterfield, who headed the Portland Field Office. We cooperated on work at areas like Champoeg State Park, where John Hussey did history. The NPS was also involved in planning work for the Columbia Gorge, where Neil was particularly involved. I also remember their assistance in what is now Lake Owyhee State Park. The were also involved in the transfer of lands at Silver Falls Recreation Demonstration Area developed by the NPS to the state parks. Even after that, there were concerns about the management of the park because there is a reversionary clause on the transfer. For example, in one place there was land within the RDA that state park officials decided they wanted to sell in order to buy in holdings located in the smaller area that’s now the state park. They sold the timber on part of the RDA with permission from the NPS and bought some of the in holdings in Silver Falls State Park. I was involved with the appraisal and sale.

How well did you know Sam Boardman?

Sam Boardman retired in 1950 after 21 years as state parks superintendent. The parks for Sam were his whole life. After he retired, he used to come down to the office. He was writing a series of articles which have become kind of a classic and were published later by the Oregon Historical Society (2). They were about various parks and how he had acquired them, the acquisition part being what mainly concerned him. Consequently he used to come by where I worked. As a matter of fact, the main reason he came in there was because we had a spittoon he could use. He chewed tobacco and he’d sit there and talk with us and occasionally spit. He’d give us his ideas about how we ought to develop the parks. I guess that’s probably the thing that stimulated my differences with his successor. We were very far apart on developing some of these key areas, like Oswald West, Cape Lookout, Honeyman, Silver Falls and some of these other places where there was a desire to do more clearing as a prelude to development.

Boardman seems more connected with the Mather school of developing park areas, where you develop places only when necessary.

Yes, I think that’s right. But the unfortunate thing about Sam’s acquisitions is that all he did was get the key feature of these parks. He didn’t obtain additional service areas. There is of course, a real problem with developing within your key feature. The classic example of this is Heceta Head, or Devil’s Elbow State Park, in Lane County, where you’re got people parking on the beach right next to the beautiful cove there where Cape Creek goes into the ocean. You’ve got everybody right there, along with a beautiful lighthouse reservation. In that particular case, there is land east of the park where they could have put a little development and allowed for a walk down to the cove.

This reminds me of criticism directed at Oregon state parks as being too compressed along highways.

That is a problem. You’ve got to realize, however, that the parks developed with the highway system. But Oregon also has probably more access to the coast than an other state. Highways next to the ocean were built purposely in order to protect the headlands from development. State parks were always directly related to the highway. Where they had parks that were away from the highways, like Golden and Silver Falls, in Coos County, the county had to declare their road to them a secondary state highway. The Highway Commission could then justify giving money to the park.

I’ve noticed that Cape Blanco is one of the few parks away from the highway and it is beautiful.

That’s a good example of a later acquisition. When Boardman was doing it, he did acquire an area north of there. It’s a place he called Henry Newbugh Park and now called Floras Lake. Sam acquired it primarily because of the unusual biological combinations of plant life, so it never was really developed. But Curry County has an airport right in the park. I think at the time Sam was acquiring land he always felt that you could get the service area later. He even says this in some of this writings. But prices are now so high and the demands for other things are so great that you can’t really justify spending the money on it.

The state seems to have relied more on donations than outright purchase up to the 1960’s.

There was some attempt to aggressively buy land in connection with the highway right-of-way. The Highway Commission would buy a piece for the highway and the balance would become part of a state park. You see, up until 1980, all the money for state parks came out of the highway fund. So everything had a be justified in terms of its highway orientation. In those days you didn’t go to the legislature and ask for land acquisition money. You went to the Highway Commission and they’d decide whether to fund the project.

That answers my question about why Oregon doesn’t have large areas like California does, as with parks such as Anza-Borrego.

Yes, we don’t have anything of that size. One of the places that might have been a possibility for large park would have been Steens Mountain in the southeastern part of the state. I made a study of that once for the Bureau of Land Management back in the 60’s. It would have been a logical state park. But the Highway Commission would have had to trade with the BLM to do it. Under the system we’re talking about, this would be a problem since the area is not near the highway system. If you look at the history of how the parks were developed in this state, you can see from the earliest time that the objective was to provide for scenic beauty in relation to the highway system.

Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr. Oral History Interview

So McKay was development-oriented?

Yes. He subsequently became Secretary of the Interior in 1953. Of course, I think the big thing there was to get people to spend the night in Oregon. The argument was that they would drive from California to Washington without stopping because they couldn’t here. We had some wonderful areas that we could develop, so we did. About 1953 I got into a series of differences with Armstrong, who was parks superintendent. This was particularly acute over the development at Oswald West State Park, and then called Short Sand Beach, about whether to put a road down at the beach. Actually it centered on a latrine that’s now covered by trees. As a result, I was told that either you go along with us, or we’ll get somebody else.

I had already been thinking about doing graduate work so that I could teach. My interests centered on forest recreation. So I stayed with the state, working as the forester for the Highway Commission until 1959. That meant that I worked with the parks on blow downs and this kind of thing. I also worked on the freeway system, on what is now I-5 and I-84. This was when they were relocating these routes and buying property that was forested. I would appraise the timber. There were a lot of blow downs and we had salvage sales. I stayed with that until going to the University of Montana as an assistant professor of forestry, having done graduate work at Oregon State on a night school basis. From Missoula I went to the University of Minnesota as professor of forestry in 1966. I again headed up a program in outdoor recreation, called recreation resource management. I stayed with that until I retired in 1986.

Did you have any contact with the NPS during your time with the state parks?

Yes. We worked with the National Park Service, especially Neil Butterfield, who headed the Portland Field Office. We cooperated on work at areas like Champoeg State Park, where John Hussey did history. The NPS was also involved in planning work for the Columbia Gorge, where Neil was particularly involved. I also remember their assistance in what is now Lake Owyhee State Park. The were also involved in the transfer of lands at Silver Falls Recreation Demonstration Area developed by the NPS to the state parks. Even after that, there were concerns about the management of the park because there is a reversionary clause on the transfer. For example, in one place there was land within the RDA that state park officials decided they wanted to sell in order to buy in holdings located in the smaller area that’s now the state park. They sold the timber on part of the RDA with permission from the NPS and bought some of the in holdings in Silver Falls State Park. I was involved with the appraisal and sale.

How well did you know Sam Boardman?

Sam Boardman retired in 1950 after 21 years as state parks superintendent. The parks for Sam were his whole life. After he retired, he used to come down to the office. He was writing a series of articles which have become kind of a classic and were published later by the Oregon Historical Society (2). They were about various parks and how he had acquired them, the acquisition part being what mainly concerned him. Consequently he used to come by where I worked. As a matter of fact, the main reason he came in there was because we had a spittoon he could use. He chewed tobacco and he’d sit there and talk with us and occasionally spit. He’d give us his ideas about how we ought to develop the parks. I guess that’s probably the thing that stimulated my differences with his successor. We were very far apart on developing some of these key areas, like Oswald West, Cape Lookout, Honeyman, Silver Falls and some of these other places where there was a desire to do more clearing as a prelude to development.

So the state parks are an outgrowth of good roads and a movement to protect at the beauty along them.

Yes. We have corridors, like the Van Duzer on the way to the coast, which is a good example (3). But it also demonstrates where the highway maybe the kiss of death in the long run. This is because as you widen the highway, you lose more old growth trees. It is a real problem because the Van Duzer represents one of the very few old-growth areas in the Coast Range that the public can see.

Those large trees remind me of a question I had regarding Steve Mather’s involvement in the Save-the-Redwoods League.

Mather was involved with my grandfather, Madison Grant, and Henry Fairfield Osborn in setting up the League. This organization was very influential in getting the state park system going in California for a couple of reasons. One was that they had a lot of strong support from the east coast, but a more important reason involved dedicating redwood groves in response to donations. This was an absolute winner.

Sort of like buying a brick.

That’s right. What could be better than getting a sacred grove named after somebody? This was helped along by a bill which passed the state legislature in the 1920s. It provided matching money, so that the state furnished money to save the redwoods. When some wealthy family like the Rockefellers bought a big grove, the money went twice as far. They would never have been able to acquire what is now Humboldt Redwoods State Park without this formula. The League also bought a lot of land in the 1930s when the lumber industry was trying to get rid of it because they couldn’t pay the taxes on their property.

The League was very influential primarily because you had a lot of powerful people in the state at that time who was also involved with the state parks. Grandfather was one of these people, as was William E. Colby of the Sierra Club, and Joseph R. Knowland, who I think owned the Oakland Tribune. There were also people from Southern California who were involved in the League, such as Major Frederick Burnham and others. Mather had Eastern connections with people and arranged to have a few of them give money for the first groves bought by the League. The first was called the Bolling Grove and was dedicated in 1921. I think Bolling was a high ranking officer who was killed in the First World War. Mather knew his family or at least got in contact with them. I believe Mather was a key in getting Rockefeller interested in the League.

Did the League support the expansion of Sequoia National Park in 1926?

I know they have been concerned about the management of the Giant Sequoia. I also know that they were very influential in getting the Point Lobos Reserve south of San Francisco, on the Monterey Peninsula. This had no direct connection with the redwoods, but they got involved anyway (4).

I know that landscape architects have played an important role in the NPS, but have they been influential in the state parks of California and Oregon?

They have been important in California, but I can’t say to what degree. They have had a lot of influence in Oregon, though only one of them—Mark Astrup—ever served as director. Landscape architects have had key roles in Oregon’s state park planning, but this is more of a staff function than an administrative one.

Did state park planners have a role in the transfer of the parks in the John Day Fossil Beds to the NPS?

I don’t know too much about this. It happened during the period when I was away from Oregon. I do know what Dave Talbot says about it. When I worked as a planner we had a series of properties over in Grant and Wheeler Counties. Sam didn’t see any importance in developing the Painted Hills and Picture Gorge areas. But these areas really had national significance, so Dave worked with Mark Hatfield to get them transferred over to the Federal Government so that a national monument could be create. As a matter of fact, I happened to be in Washington at the time of the Senate hearings on this back in 1974. I was there to attend some [National] Parks Association meetings (5). I remember the discussion about the transfer and think it’s been for the best, because the Park Service has been able to bring the fossil beds together as a unit. They have access to money that never would have been available through the state. It is too far away from Salem and the use never approached that of places on the coast.

On a somewhat different subject, could you give me an outline of your father’s career?

Dad graduated from Cal with a degree in forestry and a degree in mathematics. He subsequently worked as a logging engineer for the Madera Sugar Pine Company around Yosemite laying out logging railroads. He then went to Portland to work with Mason and Stevens in their consulting firm. Mason had been one of his professors at Berkeley and was a very able fellow (6). Incidentally, this is now the leading consulting firm in forestry on the West Coast. It has been for a long time. In the late 1920s, dad was transferred to San Francisco to set up an office for the firm. When the depression came in ’29, the firm was closed and dad went to work for himself as a consultant. He was doing quite well with that when the Civilian Conservation Corps was created in 1933. Dad then had the opportunity to coordinate CCC work for the Park Service as the Regional Officer in San Francisco. So he really started out in a key job and was there until 1937. At that point the superintendent of Yosemite, Colonel Thomson, died. Father had taken one of those civil service exams which allowed him to apply for the job. He was hired and worked there until 1941 when he became regional director in Omaha. In those days that region included all of the Park Service areas in the Rocky Mountains and the middle west. He went to San Francisco in 1950 as regional director. His oversaw Park Service areas in the western states as well as Alaska and Hawaii and stayed there until his retirement in 1963.

There wasn’t any particular parallel with my uncle’s work in the Geological Survey. Charlie was primarily a scientist who spent most of his career in Nevada studying the stratigraphy of the state. I think he worked on strategic minerals during the war. Before the war I was with dad in Yosemite and finishing high school. I’d say his administration of the park was quite different than Colonel Thomson’s. Father was the first one to really challenge the Yosemite Park and Curry Company to conform to their contract.

Thomson had been at Crater Lake before going to Yosemite.

The first Park Service superintendent at Yosemite was W.B. Lewis, who had been appointed by Mather. Thomson followed him. Dad was very interested in trying to get the Park Service to assert themselves in administering the park. He built a loyal advisory committee around himself which included Colby, Joel Hildebrand, Bestor Robinson and some other people that my grandfather had known. They came up with the idea of trying to get some of the things out of the valley which, of course, the YP&C Company very much opposed.

Would he have objected to the Fire Fall?

I don’t think he really objected to the Fire Fall. But he recognized that these things didn’t really have a place if you were going to protect the area as a national park. I used to be a ski racer when I was a teenager. The concessionaire saw Yosemite as ranking with Sun Valley as a ski areas and these were the two biggest places before the war, except for the areas in Vermont. Father didn’t think this belonged in a national park and I believe he was right. It may be all right to have a minor thing, but to try and pattern Yosemite after St. Moritz in Switzerland was too much.

This type of promotional activity might explain why downhill skiing was popular at Crater Lake for a time.

I think that’s a good point. During the period that Newton Drury was director of the Park Service there was an attempt to move away from having the parks be attractions for things that they are not really set up to do. Badger Pass in Yosemite has no relation to the values of Yosemite Valley such as the glaciation, the geologic scene, or the Mariposa Grove. These are the feature for which the park was preserved. The ski program at Yosemite has actually expanded since the war. It isn’t in competition with Aspen and Vail and places like that, but for California it is still a major ski area.

What sort of problems would your father have dealt with as regional director in San Francisco?

I think that he covered a lot more territory than regional directors do now. He probably dealt with a lot more mundane problems. They are much more complicated today.

Was your father interested in state parks at that point?

Yes. This continued from what he did in the 1930’s. I remember the Mount Diablo projects and can remember coming to Oregon at about that time, but don’t remember the specifics. I found a lot of correspondence while doing my state park history between Dad and Sam Boardman that concerns the management of CCC projects in Oregon. He certainly was involved with planning for awhile because his name appeared on a lot of the things as the top administrator. He didn’t have much of a role at Champoeg. Some people in his office were working on those projects.

I’ve noticed that he took some slides of that area. They are in the stat library.

He was also involved with parks after his retirement. He went to work with Drury at the Redwood League office in San Francisco. Father worked as a consultant and did this until a few years before his death in 1981. Drury worked until a couple of weeks before he died.

When was that?

1978.

I’ve noticed Drury is still quoted a lot on Sierra Club calendars and publications like that.

Oh yes, he was a very interesting guy.

This is a continuation of an oral history interview with Larry Merriam on November 26, 1988, in Corvallis. We are starting the third section, which concerns the career of John C. Merriam. How did your grandfather obtain a teaching post in Berkeley?

He obtained his bachelor’s degree at age 18 from Lenox College in Hopkinton, Iowa. Grandfather subsequently came west to Berkeley with his parents. My great grandfather was interested in the banking business. He was in contact with the man who later become grandfather’s father-in-law. But the banking business didn’t work out for him and he went back to Iowa. Grandfather, however, stayed there and started graduate studies under Joseph LeConte, the famous professor who came from the University of South Carolina after the Civil War to be the grand man of geology at the University of California.

When did your grandfather do this?

This was in the late 1880s. In those days, there were not too many Ph.D. programs in this country and the thing to do was to go to Europe. And grandfather went to the University of Munich, and did his doctoral work under Von Zittel. His thesis is in German. I saw the dissertation when I gave a paper in Muchich many years later. His degree was granted in 1894 and from there he become an instructor at the University of California, rising to the rank of professor by 1912. This is a list of his papers from the Bancroft Library and it tells a little bit about his career. He came to the University of California as instructor of paleontology in 1894 and became Dean of Faculties in 1920. In 1921, he left to become President of the Carnegie Institution in Washington and stayed there until 1938. He was also a regent of the Smithsonian Institution from 1928-1938.

When did he first come to Oregon?

His first trip to Oregon probably was in 1899 expedition to the John Day country with his student from Berkeley. That was written up by Loye Holmes Miller in a monograph published by the University of Oregon some twenty years ago (1). It’s an interesting story because he come up from California I think by train. His students came by sea which I guess was less expensive. They met in Portland and took a steamer up as far as The Dalles. They then had a wagon team for travel inland to fossil areas. An interesting sideline to this occurred on a Sunday morning in Antelope, where we had all the concern about the Rajneshees a few years ago. Although it was a Sunday morning, all the saloons in Antelope were active. Grandfather found some fellow who was staggering along, leading his horse. When Grandfather and the students reached him, they propped the man up against a fence post and before leaving him tied his horse to the fence. They figured that was a good way to get him to sober up. This was typical of my grandfather ‘s Presbyterian background. He did not have a very high regard for drinking or any type of carousing, particularly on Sunday.

Why did he spend some of his summers in Oregon when he was President of the Carnegie Institution?

That is an interesting aspect. He had an arrangement with the Carnegie family which allowed him to take part of his time off in the summertime, when it is so hot in Washington. If you’ve been to Washington, then you know that between May and end of September, it can be very hot and humid. If you’re a westerner, it’s pretty hard to get used to. What grandfather used to do was to have the Institution’s annual meeting before late spring so that he could leave his office. He would take his personal secretary, a man by the name of Sam Calloway, who also doubled as a chauffeur. Grandfather would arrange through my father to have a seven passenger Packard limousine available for them through Earl C. Anthony in Oakland and then drive around and do all his work here in California. At the same time that he was doing that, he was not really away from Carnegie Institution because he was taking care of the Carnegie’s maters having to do with Cal Tech in Pasadena. He could also tie in his Redwood League work with Newton Drury and activities with my father. So that was an interesting split in his activities. In a way, I did that myself. I took my summer off from the Midwest to come to California for a month during the summer to see my family.

Did you get to accompany him on some of his trips to various parks and study areas?

Not really. By the time I was fifteen, he retired from the Carnegie Institution. At that time I was somewhat accepted as an adult in my family, though you did have to prove yourself. I can remember the Dedication of Humboldt Redwoods State Park at Bull Creek Flat in 1931. My folks went with him and then I was ferreted off to a lady that looked after me there in Berkeley. In retrospect, it would have been a very interesting thing to have been there because that was the dedication at the Founders Grove. In 1932, we spent the summer in Benbow. Do you know where that is? It’s in Humboldt County, south of Garberville. Anyway, it’s a fancy hotel now and very expensive. I took my daughter there a few years ago, along with her daughter and my wife Kathie. Benbow was the site for the Council meeting of the Redwood League. So grandfather would usually arrange to stay there in the hotel, or one of the cabins. That summer we had a cabin which we rented in that same general area and so I did see grandfather a bit at that time when he was doing some Redwood League business. Drury had a cabin at Benbow, too. So the Drury family and our family were all there together. But I don’t remember even going to the hotel. As a matter of fact, my first remembrance of the hotel was that my wife and I spent a night there on our honeymoon in 1947.

Grandfather used to talk with me about parks and study areas. We would have discussions about his work and his thoughts about parks. In the last year of his life, I did a lot of philosophical reading when I was at sea in the Navy and I discussed some of these things with him on the occasion that I saw him in Berkeley.

Lawrence C. Merriam, Jr. Oral History Interview

Was your father interested in state parks at that point?

Yes. This continued from what he did in the 1930’s. I remember the Mount Diablo projects and can remember coming to Oregon at about that time, but don’t remember the specifics. I found a lot of correspondence while doing my state park history between Dad and Sam Boardman that concerns the management of CCC projects in Oregon. He certainly was involved with planning for awhile because his name appeared on a lot of the things as the top administrator. He didn’t have much of a role at Champoeg. Some people in his office were working on those projects.

I’ve noticed that he took some slides of that area. They are in the stat library.

He was also involved with parks after his retirement. He went to work with Drury at the Redwood League office in San Francisco. Father worked as a consultant and did this until a few years before his death in 1981. Drury worked until a couple of weeks before he died.

When was that?

1978.

I’ve noticed Drury is still quoted a lot on Sierra Club calendars and publications like that.

Oh yes, he was a very interesting guy.

This is a continuation of an oral history interview with Larry Merriam on November 26, 1988, in Corvallis. We are starting the third section, which concerns the career of John C. Merriam. How did your grandfather obtain a teaching post in Berkeley?

He obtained his bachelor’s degree at age 18 from Lenox College in Hopkinton, Iowa. Grandfather subsequently came west to Berkeley with his parents. My great grandfather was interested in the banking business. He was in contact with the man who later become grandfather’s father-in-law. But the banking business didn’t work out for him and he went back to Iowa. Grandfather, however, stayed there and started graduate studies under Joseph LeConte, the famous professor who came from the University of South Carolina after the Civil War to be the grand man of geology at the University of California.

When did your grandfather do this?

This was in the late 1880s. In those days, there were not too many Ph.D. programs in this country and the thing to do was to go to Europe. And grandfather went to the University of Munich, and did his doctoral work under Von Zittel. His thesis is in German. I saw the dissertation when I gave a paper in Muchich many years later. His degree was granted in 1894 and from there he become an instructor at the University of California, rising to the rank of professor by 1912. This is a list of his papers from the Bancroft Library and it tells a little bit about his career. He came to the University of California as instructor of paleontology in 1894 and became Dean of Faculties in 1920. In 1921, he left to become President of the Carnegie Institution in Washington and stayed there until 1938. He was also a regent of the Smithsonian Institution from 1928-1938.

Hall was the Park Service’s chief forester and head of its education program in the 1920s.

Yes. In fact, the Park Service had an office at the University of California in Berkeley down on Fulton Street. As you have said, the Carnegie Institution was able to funnel some money through National Academy of Science or by other means to help, the Park Service, with things like the Sinnott Memorial and the Yavapai Station at Grand Canyon. He influenced operations in that respect, as well as being the chairman of this committee.

We talked earlier about how grandfather sort of lost out during the 1930s once Mr. Albright became director. This rather ties in with some correspondence that I have between grandfather and Newton Drury, who later was director of the Park Service. Grandfather became concerned about the Park, Parkway and Recreation Area Study Act and how the parks could be changed from the old classic areas to this idea of bringing in Civil War battlefields and recreation areas. He mentioned specifically the city parks in Washington. His position tended to be counter to the direction the Park Service was going, particularly in the 1930s under the ECW program in the Roosevelt era. At that point, his direct influence on park matters probably lessened somewhat. When Drury became director in 1940, grandfather had more access to discussion about the management of the national parks since they had always been fairly close due to their work in the redwoods and with the state parks in California. I remember some discussions when father was superintendent of Yosemite that concerned the story of granite, which grandfather wanted interpreted. This is not in the park itself, but down the Merced River Canyon below El Portal. Grandfather seems to have had some professional differences with Dr. Francois Matthes, who was probably the leading expert on Yosemite’s geology, over which over which formations were critical in the development of the area around Yosemite. Grandfather was also involved with the field school in Yosemite Valley. He used to talk to them about various kinds of geological problems.

Several other things affected the amount of influence he had in the parks. One was that he retired from the Carnegie Institution in 1938. This terminated his ability to provide funding for projects. Another factor was my grandmother’s death in 1940. Grandmother was a great influence on him and had accompanied him on most of his travels to the national parks. As a result, he didn’t travel around quite so much to the parks. He became an adjunct professor at the University of Oregon in 1939, though a courtesy appointment much like the one I have here at Oregon State. When a person retires, however, their influence is not as great as it was before. I’ve seen letters between my father and Newton Drury that suggest Drury did not want my grandfather telling him what to do at every turn, as grandfather did with his son. As a result, some differences developed because grandfather was a strong personality. He had views that didn’t allow for much compromise.

Why did your grandfather turn down the offer to be one of Wilderness Society’s founders? What was his attitude toward the concept of wilderness?

First of all, I think he would have seen wilderness as a natural thing. In those days, there was a lot more undeveloped country than there is now. To my knowledge he wasn’t a rigorous hiker or a masochist of the type that Bob Marshall was, or even John Muir. He did do hard hikes in his early years in places like the John Day country and the valleys in Nevada. He would probably would have seen things a little different than Marshall or Muir. I think he would have been more apt to see it in terms of the way you could get the public to go along with the ideas you had. I think his ideas about national parks would be viewed as moderate today.

As for the Wilderness Society, I didn’t learn too much about this until just recently. So I can only speculate on why he didn’t become a founder. My suspicion is that grandfather was pretty conservative and he also played his political cards pretty carefully. In the 1930’s, Marshall was a person that would have been good to write to, but not the kind of a person that grandfather would want to be perceived as being close to. What I am referring to is the impression of Marshall being what we’d call today a super liberal.

People like Robert Sterling Yard did not seem to have this problem.

Yes, because they were in similar organizations. Madison Grant, one of the founders of the Redwood League, was another person that grandfather had to be really careful with. I’m not sorry about getting this on paper, because I found some material in the files in the Library of Congress where Madison Grant tried to get grandfather involved in one of his white supremist schemes and grandfather stayed completely clear of it. So this suggests to me that he wasn’t interested in anything that would compromise his position as President of the Carnegie Institution. This is to his credit because it would affect the Carnegie family as well as himself. The other thing which factored in here was that he was just too busy to be involved, as you see from his letters. He was always going a million miles a minute. He did that right up until the time he died. From my knowledge, grandfather was on friendly terms with Robert Sterling Yard. I think there are a lot of views about Yard and, as you know, I was a trustee of the Parks Association, so I knew about him. Yard had some very difficult times financially with that organization. Grandfather was one of the people who, along with Herbert Hoover (who was once president of it, as a matter of fact), bolstered it up occasionally. I think grandfather supported a lot of Yard’s ideas, but sometimes Yard went quite a ways out on a limb on controversies involving concessionaires and Park Service leadership.

Did your grandfather know John Muir?

I don’t know if I mentioned to you a little story told to me by my uncle. At one time grandfather may have been enamored with one of Muir’s daughters before he met my grandmother. Once he was thinking of going to see Muir when on a ridge above Martinez, but then decided to go elsewhere. Grandfather knew him on a business basis as a paleontologist.

So he wasn’t involved in the Sierra Club during the early days?

He was involved in the Sierra Club to the degree that he became an honorary vice-president of it. I think this was probably about the time when grandfather became President of the Carnegie Institution, but I’m not sure about that. And he was a honorary member for a long time. Dad was an honorary life member.

But he wasn’t in the early Sierra Club.

Not at the time when Muir, William Fredrick Bade, and Colby founded it. But he knew many of them quite well, particularly Colby.

How did your grandfather develop interpretation in the national parks while being in an advisory role?

We’ve talked about that a little bit. He had a particular interest in places characterized by their geology, such as Crater Lake, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone.

That question is connected to some correspondence I’ve seen where your grandfather suggested that naturalists should be posted in parks for long periods of time, maybe ten to twenty years?

Of course, this kind of thing would be counter to the Park Service’s practice of moving people around from place to give them experience. For a person to stay any length of time in a park, even back in the 1930s, was thought to be an indication of their being denied promotion.

I wondered if the Park Service borrowed this idea from the Forest Service?

I really don’t know about that. It’s done in all these big agencies. They don’t want employees to become little kings in their own areas. Part of it is protection of the agency.

What was your grandfather’s philosophy about nature?

My impression of it is that he developed a lot of his ideas from the writing of Wordsworth. He was very much taken with Wordsworth’s poetry. I remember discussing some of that with him. He was also interested in the ideas of people like Muir, Emerson and Thoreau. Grandfather was very philosophical in his interests, with respect to understanding a greater meaning to life and that sort of thing. I have a feeling that he really saw God revealed in nature, particularly in the Redwoods and in the beauties of the Grand Canyon and so on. If you read his writings, this comes out. He also was influenced by Goethe’s writings. I think the title of The Garment of God actually comes from a line by Goethe (2).

Did this have any effect on his ideas about developments in national parks?

Grandfather had very strong beliefs, which put him at odds with the general run of Park Service administrators—particularly those like Conrad Wirth. Unlike many who emphasize development in parks, he believed that the natural scene, if interpreted properly, could provide people with an understanding which would allow them to go away refreshed and be better people. A national park could be a better form of classroom if you take this to its logical conclusion. That’s a hard thing to say. I recollect that studies about interpretation in the national parks generally show that something like ten percent of visitors to places like Yosemite Valley go to the interpretive program. Unfortunately it isn’t very high.

In some cases even less.

Many times the people who got to them are ones who already understand something about the park. There are a few exceptions. I’m thinking of Norris Geyser Basin in Yellowstone, where interpreters have done a good job of reworking what was an awful museum there. It’s now a wonderfully illustrated description of the geyser basins, and then you walk right out of the interpretive center to see the basin itself. They’ve now developed these kiosks into big things. You go into them and see a little slide show on the thermal activity in Yellowstone and the doors of it open just in time to allow you to see an eruption of Old Faithful. That’s the way you get lots of people to see things. The average guy is looking for the thrills, the fast-moving things, like Old Faithful erupting. Then they want to know where’s the john and how to reach the hamburger stands. That’s too bad. Like the woman who went to Grand Canyon and thought that was an awful big ditch. What does it mean? Now that we’ve seen this, what else is there? Actually, grandfather’s vision of what people would get from a park is probably conditioned largely on his own experiences, his writing and his associations with people who, by and large, were people of great importance at that time. I don’t think he really ever had any understanding of the general public.

So he was somewhat insulated?

Yes. I think that’s true of academicians, that they tend to be that way.

Footnotes:

- Langille, following the lead of William Gladstone Steel, was among the original Mazamas. His job with the state parks included writing histories of the various state parks. These mimeographed bulletins were intended as references for state parks personnel and to provide interpretive information for visitors and the media.

- Boardman, Oregon State Park System (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1956; reprinted from the Oregon Historical Quarterly 55:3 (September 1954), pp.23-28.

- On state highway 18 between Otis and Grand Ronde.

- One of the key reasons involved remnant stands of Monterey Cypress.

- It is now known as the National Parks and Conservation Association.

- David T. Mason is probably best know as an advocate for sustained yield forestry.

Footnotes: from second interview

- Miller, Journal of First Trip of University of California of John Day Beds of Eastern Oregon, edited by J. Arnold Shotwell, Bulletin 18 of the Museum of Natural History, University of Oregon, Eugene, December 1972.

- John C. Merriam, The Garment of God (New York: Scribners, 1943), p.2.

Other pages in this section

- Crater Lake Centennial Celebration oral histories

- Hartzog – Complete Interview (PDF)

- Jon Jarvis

- Albert Hackert and Otto Heckert

- Hazel Frost

- James Kezer

- F. Owen Hoffman

- Douglas Larson

- Carroll Howe

- Wayne R. Howe

- Francis G. Lange

- Marvin Nelson

- Doug and Sadie Roach

- James S. Rouse

- John Salinas

- Larry Smith

- Earl Wall

- Donald M. Spalding

- Wendell Wood

- John Lowry Dobson

- O. W. Pete Foiles

- Bruce W. Black

- Emmett Blanchfield

- Ted Arthur

- Robert Benton

- Howard Arant

- John Eliot Allen

- Obituary Kirk Horn, 1939-2019

- Mabel Hedgpeth

- Crater Lake Centennial Celebration oral histories

- Hartzog – Complete Interview (PDF)

- Jon Jarvis

- Albert Hackert and Otto Heckert

- Hazel Frost

- James Kezer

- F. Owen Hoffman

- Douglas Larson

- Carroll Howe

- Wayne R. Howe

- Francis G. Lange

- Marvin Nelson

- Doug and Sadie Roach

- James S. Rouse

- John Salinas

- Larry Smith

- Earl Wall

- Donald M. Spalding

- Wendell Wood

- John Lowry Dobson

- O. W. Pete Foiles

- Bruce W. Black

- Emmett Blanchfield

- Ted Arthur

- Robert Benton

- Howard Arant

- John Eliot Allen

- Obituary Kirk Horn, 1939-2019

- Mabel Hedgpeth