The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon With a reconnaissance of the Cascade Range southward to Mount Shasta by Howell Williams

The Structural Setting of Mount Mazama

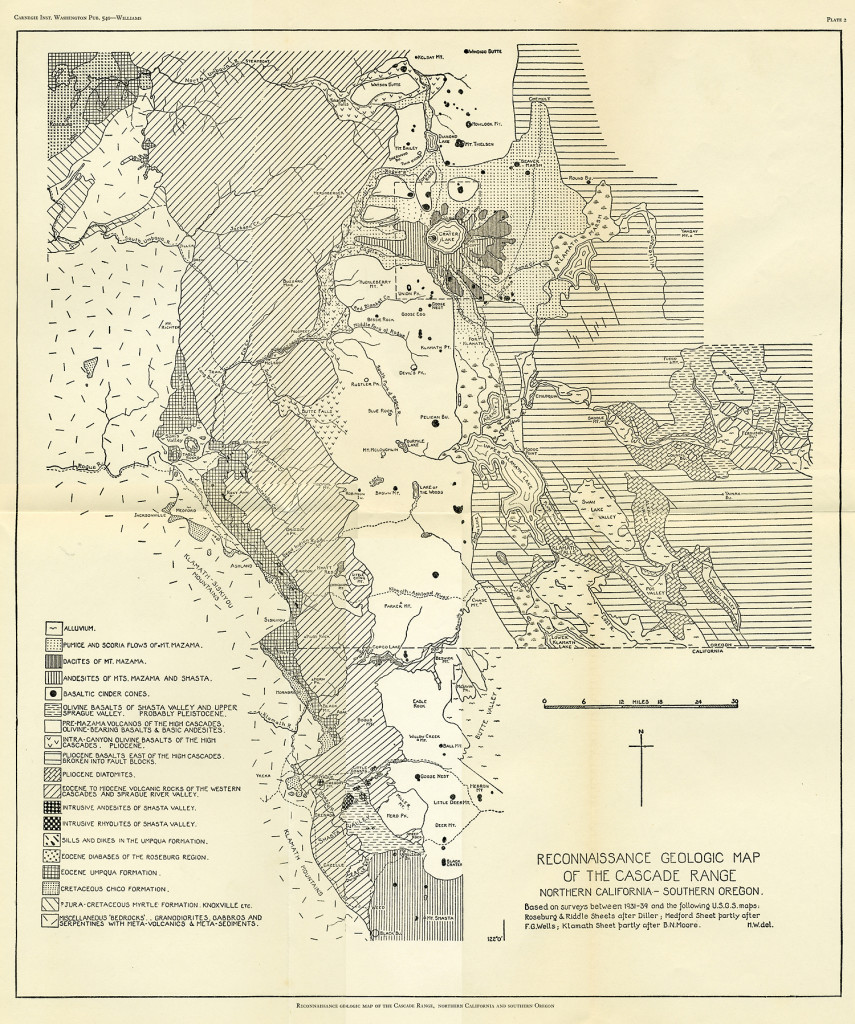

IN THE part of the Cascade Range shown on the map (plate 2), the pre-Pliocene volcanic rocks dip, in general, toward the east and northeast beneath the lavas of the High Cascades, and their dip diminishes in an easterly direction. Where they finally pass beneath the Pliocene flows, they lie almost if not quite horizontally.

Plate 2

Not only were the volcanic rocks of the Western Cascades folded at the close of the Miocene, but, as we have seen already, they were cut by a system of north-south fractures and invaded by a series of north-south stocks of diorite, around which the older lavas were widely mineralized. It was this north-south fracture system that located the sulphide areas of the Western Cascades and the position of the High Cascade volcanoes.

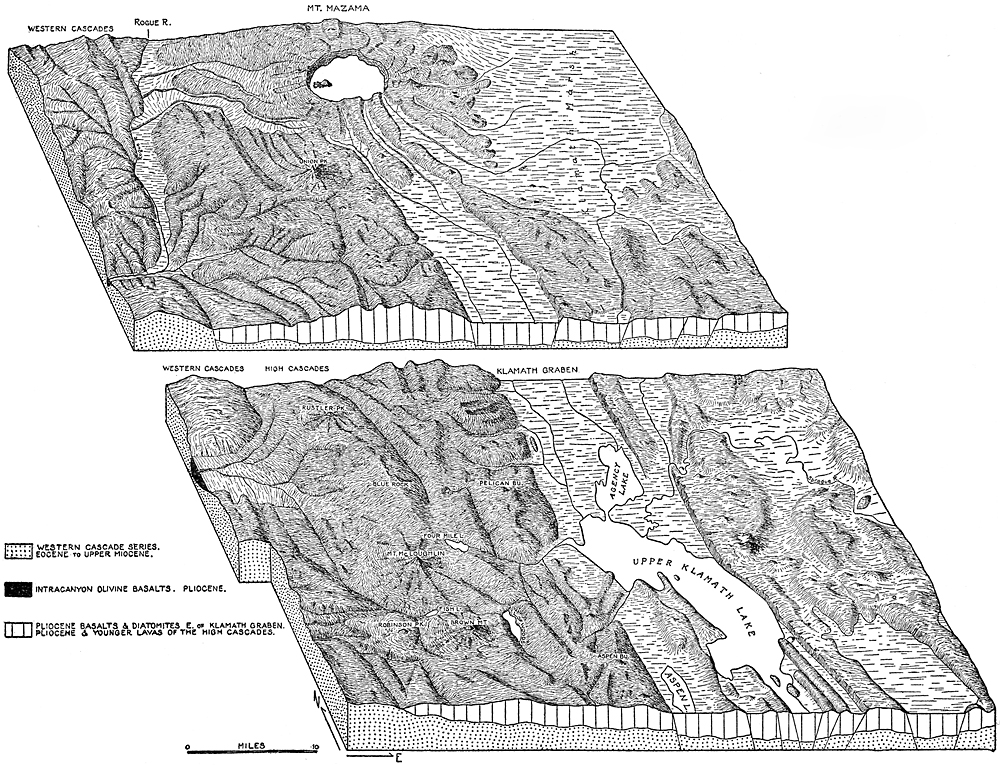

In the plateau province east and southeast of Crater Lake (see plate 5, figure 2), the trend of the faults is mainly northwest-southeast. This is clearly indicated in the region about Klamath Falls (see block diagram, figure 5).

|

Plate 5. Fig. 2. Looking north toward Crater Lake from near Fort Klamath. Valley floor covered by outwash from the Annie Creek pumice flow. In the distance area: 1, Crater Peak, a parasitic cinder cone; 2, Applegate Peak; 3, Dutton Cliff; 4, Cloudcap (peaks 2, 3, and 4 lie on the rim of Crater Lake); 5, Grayback Ridge; 6, Mount Scott; 7, fault scarp in pre-Mazama, Pliocene olivine basalts. |

Immediately south of Crater Lake, the edge of the High Cascades is defined by a north-south fault forming the western boundary of the Klamath graben. Near the California-Oregon line, this fault breaks into a group of minor faults which are offset by the northwest-southeast system of fractures. Indeed, intersection of north-south with northwest-southeast fad seems to be characteristic of the border zone between the High Cascades and the plateau to the east. Moreover, as they approach the High Cascades, several of the northwest-trending faults swing to a north-northwest direction. This is noticeably true of the faults forming the eastern border of the Klamath graben.

Possibly the position of the younger cones of the High Cascades is determined by intersection of the north-south fractures with these oblique faults approaching from the east, and possibly Mount Mazama itself lies at the crossing of the main High Cascade fracture with the largest of the oblique fractures, that forming the eastern boundary of the Klamath trough. Where this oblique fracture disappears beneath the lavas of Mount Mazama at the southeast corner of the National Park, it is directed toward the center of Crater Lake, and if it continues thus far it mum there intersect the north-south fault that forms the western wall of the Klamath graben.

The faults of the Klamath region cut Pliocene basalts and diatomites, and, according to Moore,1 they are “probably no older than uppermost Pliocene.” Many of them are marked by scarps which seem too fresh to be older than Recent.

***previous*** — ***next***