|

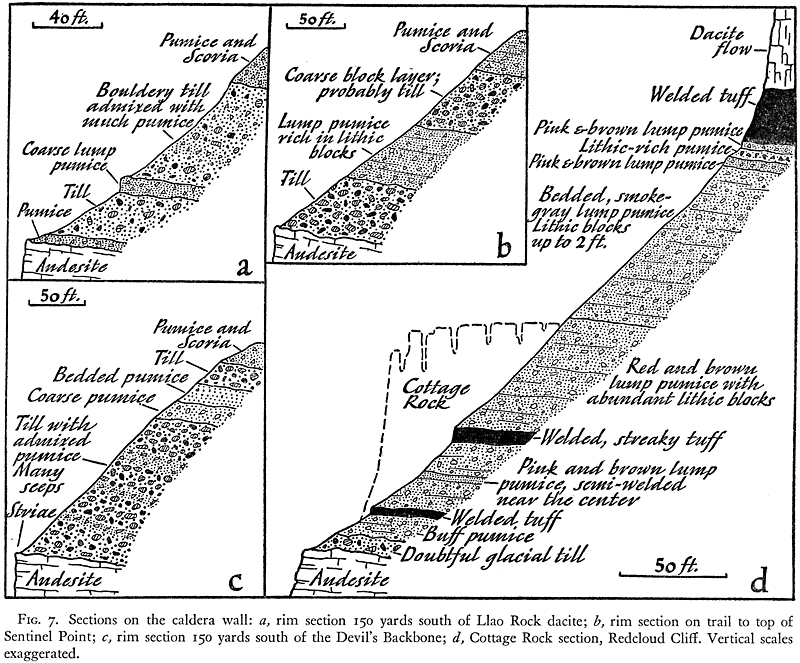

Fig. 7. Sections on the caldera wall: a, rim section 150 yards south of Llao Rock dacite; b, rim section on trail to top of Sentinel Point; c, rim section 150 yards south of the Devil’s Backbone; d, Cottage Rock section, Redcloud CW. Vertical scales exaggerated. |

Between Cottage Rock and the great V-shaped cliff of Redcloud, the deposits of dacite pumice are divided by a wedge of andesitic lava, as they are in the sections at Pumice Point, Cleetwood Cove, and Llao Rock. The presumption is, therefore, that all these pumice deposits belong to the same general period of transition in Mazama’s history, before the eruption of intermediate magma finally gave way to eruption of dacite flows and basaltic scoria.

Many interesting problems are raised by the pumice and tuff deposits of the Cottage Rock section. Eruptions adequate to form 200 feet of ejecta on the caldera walls must of course have laid down a thick sheet over most of the volcano. Yet no corresponding deposits can be identified with certainty on the outer slopes. Possibly the coarse ejecta in Pumice Flat, near the base of the Union Peak volcano, are of the same age. Certainly they are not products of the final eruptions of Mount Mazama, for the winds at that time were blowing in the opposite direction.

The uncompacted and well stratified lump-pumice deposits of the Cottage Rock section presumably settled from the air in showers. On the other hand, the welded tuff which alternates with them must have been erupted in quite a different fashion. Had these ejecta been thrown high above the vents, they would have lost much of their heat and gas before reaching the ground, and therefore would not have suffered the intense compaction which now characterizes them. So firmly are the constituent particles welded together, and so finely laminated is the tuff, that only microscopic examination permits one to say with certainty that the deposits are not streaky flows of dacite obsidian. In order to produce compaction of this character, the ejecta must have remained hot and gas-rich for a considerable time. Fortunately, detailed study of similar deposits from other regions supplies an answer to the problem. These welded tuffs are products of glowing avalanches (nuées ardentes). Even so, it may be asked, how could they have retained their heat and gas long enough to cause welding when two of the layers are only 3 and 6 feet thick, respectively? The answer is, not that they were formerly much thicker, but that they were immediately buried by coarser lump pumice falling from the air. While some of the ejecta rushed down the slopes of the volcano in the form of glowing clouds, the bulk was shot high above the craters and probably fell onto the avalanches soon after they came to rest. The topmost welded tuff, though much thicker, also seems to owe its compaction to rapid burial, for it appears to have been covered immediately by a thick flow of lava.