It is instructive to compare these heights with those of imaginary caldera rims on other Cascade volcanoes. For instance, if the summit of Mount Rainier were to disappear and a caldera as large as Crater Lake were to be formed, the rim would vary between 6500 and 9000 feet. More than ha& of the rim would lie at an elevation of about 8000 feet. Not only would most of the rim of the imaginary Rainier caldera be higher than that of Crater Lake, but the remnant slopes would be considerably steeper. Hence, if the original Mount Mazama had a crater commensurate with that of Rainier, its summit must have been at a much lower elevation, or well below 14408 feet.

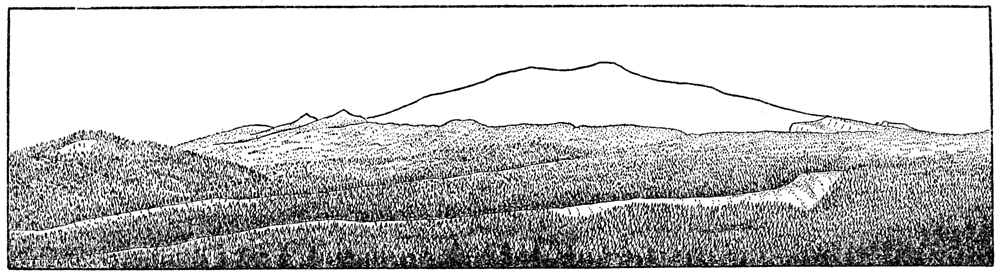

A similar conclusion is reached when comparison is made with an imaginary caldera on Mount Shasta (see figure 14).

Consider next Mount Hood, the summit of which reaches an elevation of 11,225 feet. If a caldera as large as Crater Lake were produced by the disappearance of its upper part, the rim of the depression would lie mainly between 5000 and 6000 feet, and the remnant slopes would not be unlike those of Mount Mazama. Accordingly, if the summit crater of Mazama was small it was probably higher than the top of Hood:

Several other Cascade volcanoes were examined with the same idea in mind, and the conclusion was reached that Mount Adams offers the closest comparison. Hence, Mount Mazama rose to a height of approximately 12,000 feet. The summit lay about a mile south of the center of Crater Lake.

Even if the ‘foregoing argument be accepted, it does not follow that Mount Mazama was 12,000 feet high immediately before the formation of the caldera, for after the volcano had reached this height there may have been profound collapses on its northern side at the time of the pumice explosions from the Northern Arc of Vents. The summit may also have been lowered by glaciation.

As for the shape of the volcano, it was far from being a symmetrical cone. The thick deposits of glacial debris on the northeast wall of the caldera imply the existence of deep ice-filled cirques on that side of the cone. The great U-shaped canyons on the south side must likewise have headed back into amphitheaters.

The symmetry of the cone was also marred by parasitic cones and domes associated with the Northern Arc of Vents (see figure 15). Had the lost part of the volcano been perfectly symmetrical, the glacial scratches on the caldera rim would be directed radially. In many places, such is far from being the case In particular, as figure 31 shows, the striae on the summit of Roundtop and near the Wineglass, instead of pointing toward the center of the caldera, converge toward a point a little to the west of Skell Head. Perhaps the semicircular form of Grotto Cove indicates the former existence of a parasitic cone in that vicinity, just as the scalloped margins of the caldera of Santorin are related to old cones that once rose above them and the semicircular Cleetwood Cove is related to the vent of the Cleetwood flow.

The glaciers which once choked the canyons and enveloped all save the topmost ridges had retreated to the upper part of the cone and were confined to the bottoms of the canyons. Only at three points did they extend beyond the present rim of the caldera, namely in Munson, Sun, and Kerr valleys on the south side of the mountain, where they lay in deep glacial troughs. A small corrie glacier may also have existed on the northwest side of Mount Scott, but the Union Peak volcano, if it was not entirely bare, supported only very small tongues of ice on the shady side of the summit pinnacle.

The slopes of Mount Mazama were almost barren of vegetation. A few tall trees grew on the moraines near the caldera rim, but thick forests were restricted to the foot of the volcano, below elevations of about 4500 feet. The sheet of pumice left by the eruptions from the Northern Arc of Vents had been almost wholly removed by erosion, leaving slopes of lava littered with moraines and fluvioglacial outwash.

***previous*** — ***next***