Above the columns and spires, and within a few feet of the top of the flows, there is usually a distinct pink or brick-red zone, several feet in thickness. In places, particularly above the tubular openings mentioned, the pink color is intense. Where the color is deepest, pink and brown streaks lead from cracks below. It is not only in the canyons that this feature is to be seen, for all over the Pumice Desert and along Desert Creek the deposits are characterized by pink and brown blotches, the traces of thousands of fumaroles. Usually the discoloration is most marked where scoria predominates, but it may also be seen in flows of dacite pumice, as along the Diamond Lake highway above Union Creek. The reason is of course that the scoria contains much more iron than the dacite pumice, and it was the oxidation of iron-bearing gases, probably iron chlorides, that caused the pink color. Gases rising from the hot ejecta reacted with the air and percolating rains, and the level of oxidation depended largely on the porosity of the topmost materials. Usually the pink zone is at the top of the pumice-scoria deposits or a short distance above, in the overlying layer of ash. It follows that the ash must have fallen soon if not immediately after the flows had come to rest, and while they were still emitting gas.

|

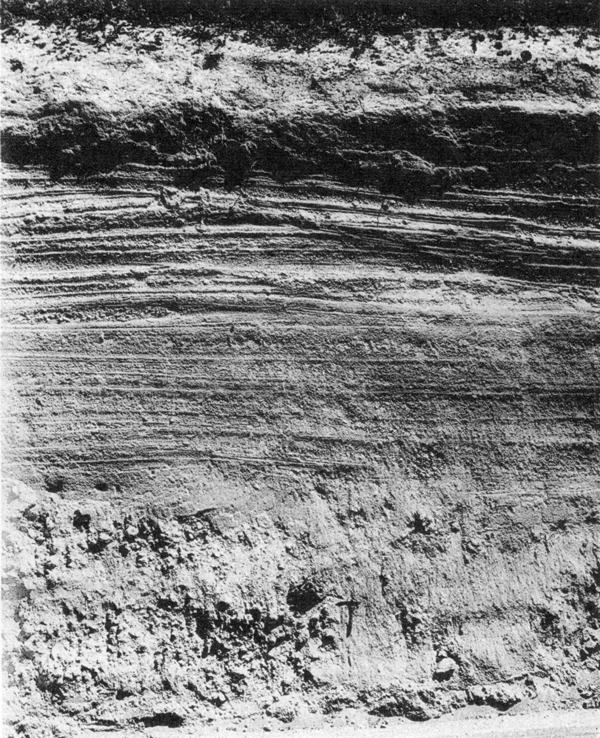

Plate 17. Fig. 3. Pumice deposits on Diamond Lake highway. At the base, 4 feet of coarse, unbedded pumice-flow deposits containing a charcoal log (near hammer). Above, bedded, fine pumice fall. The dark band near the top is the pink zone caused by oxidation of fumarolic gases rising from the pumice flow at the base. This indicates that the fine pumice fell on the flow while it was still hot. |

A spectacular instance of this kind may be seen near where the Diamond Lake highway crosses the Rogue River. Here the coarse, unbedded pumice flow is overlain by fine, well bedded pumice fall up to 15 feet in thickness (plate 17, figure 3). Yet the pink, fumarolic zone occurs not within the flow, but between 3 and 5 feet from the top of the overlying bedded pumice.

When one sees these extensive signs of fumarolic action, one is tempted to imagine how the slopes of Mount Mazama may have appeared at the close of the great eruptions. The glowing avalanches had converted the glacial canyons into wide, barren plains from which, for years, plumes of acid gas rose into the air. Long after the fumaroles had almost dwindled to extinction, the plains must have been hidden by dense clouds of steam when rains fell on the hot deposits. Nothing remained of the scant forests that had formerly clothed the lower slopes of the volcano. The ridges between the plains of “ten thousand smokes” were mantled by a gray-white pall of granular pumice. The summit of Mount Mazama had gone, leaving in its place a vast caldera, 6 miles wide. Of the long glaciers which had formerly covered the upper part of the cone, only three small relics survived in the valleys on the southern slope. It would be difficult to imagine a scene of greater desolation. For an artist’s reconstruction of the appearance of the mountain before and after the eruptions, see plate 18, figures 1 and 2.