|

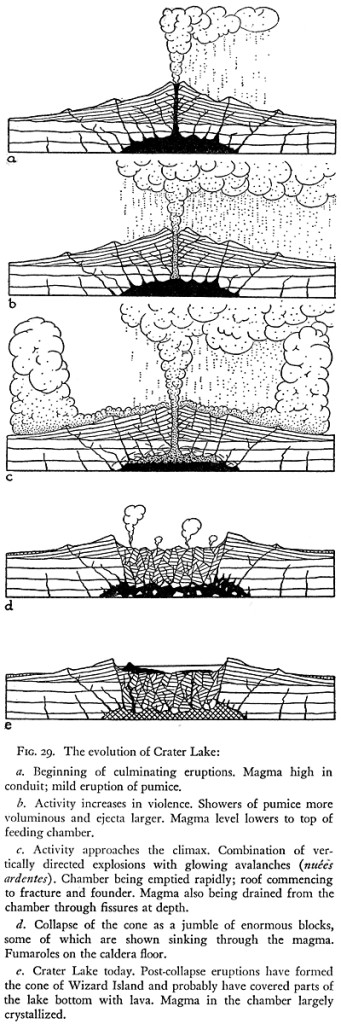

Fig. 29. The evolution of Crater Lake: a. Beginning of culminating eruptions. Magma high in conduit; mild eruption of pumice. b. Activity increases in violence. Showers of pumice more voluminous and ejecta larger. Magma level lowers to top of feeding chamber. c. Activity approaches the climax. Combination of vertically directed explosions with glowing avalanches (nuée ardentes). Chamber being emptied rapidly; roof commencing to fracture aid founder. Magma also being drained from the chamber through fissures at depth. d. Collapse of the cone as a jumble of enormous blocks, some of which are shown sinking through the magma. Fumaroles on the caldera floor. e. Crater Lake today. Post-collapse eruptions have formed the cone of Wizard Island and probably have covered parts of the lake bottom with lava. Magma in the chamber largely crystallized. |

Many years ago, Stübel urged the importance of withdrawal of magma beneath volcanoes as an explanation of calderas. Distracted, as we are bound to be, by spectacular surface manifestations of volcanic energy, we are apt to forget the equally important intrusive history at depth, for this is seldom revealed except by long-continued erosion. Lately, the brilliant studies by Bailey, Richey, and their associates among the denuded volcanoes of the Western Isles of Scotland and by Stearns on Oahu have served to focus attention on the complex and wide-spreading intrusions which take place far below the surface. The roots of ancient volcanoes commonly reveal a maze of intersecting dikes. Occasionally, underground migration of magma culminates in fissure eruptions far down the flanks of a volcano, as at Kilauea in 1924.