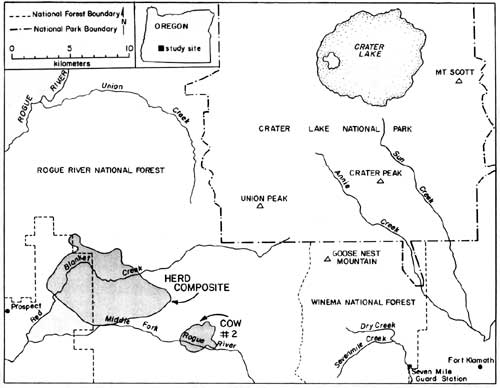

Fig. 6 – Elk home ranges, Winter 1985-86.

During 1968, early winter storms deposited 54? of snow in September and drove nine of eleven elk down Red Blanket Creek directly to the winter range. Subsequent warm weather and snowmelt allowed radio-collared elk to disperse widely back on summer range within CRLA. They may also have returned to their summer range due to hunting pressure after this heavy snow. The elk again returned to their winter range for the season after heavy snow in October, 1986.

Winter ranges of most collared elk were located at elevations between 2800? – 4000? at the mouth of Red Blanket Canyon, near its juncture with the Rogue Valley. During November 1955, 1-2 feet of snow forced the elk onto Red Blanket floodplain near Prospect. As the snows melted, the elk concentrated on the bench known as Buck Flats. This lies between the mouth of the Middle Fork of the Rogue and the mouth of Red Blanket Creek. They also moved up to the bench north of the mouth of Red Blanket Creek. Snowpack was light to absent during the winter of 1985-1986, and the elk remained above the floodplain moving upward into the old-growth forests near Bessie Rock during March and before spring migration. Two radio-collared elk, one of which was number 2 from the Crater Peak Area, wintered up the Middle Fork of the Rogue Valley (Fig. 6).

Seasonal Habitat Use Spring

Availability and use of habitats were evaluated within the composite home range of elk during spring 1986. The composited spring range of elk consisted of 83% silviculturally managed forest, 11% managed pasture, and 6% non commercial or other forest types (Table 1). Shelterwood harvesting was the most prevalent cutting prescription, although clearcuts which were common in lodgepole pine forests covered approximately 6% of the spring range. The majority of forests were dominated by white fir and lodgepole pine.

Radio-collared elk used many vegetation classes in proportion to their availability during spring (Table 1). White fir forests were the only cover type preferred by elk. White fir stands corresponded primarily to densely-stocked stands of medium-sized sawtimber, which correspondingly were also selected. Radio-collared elk avoided forest/pasture communities, which were forests within the pasture fenceline. Those stands were used intensively as bedding grounds by cattle and contained highly trampled understories. As a general diurnal pattern, elk were found in pasture, clearcuts, or partially cut stands during early morning and evening feeding periods, and they retreated to hillside forests, mainly densely-stocked stands of white fir, from mornings to afternoons. Such forests may have provided elk both with seclusion from high levels of human disturbance associated with roadways, and thermal protection from high mid-day temperatures that are common to the region.

| VEGETATION CLASS | AVAILABILITY | USE |

|---|---|---|

| Cover Type | ||

| Lodgepole pine | 14.2 | 12.3 |

| Mountain hemlock/White fir | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Ponderosa pine | 1.3 | 2.6 |

| Shasta red fir | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| White fir | 61.4 | 69.9(+)a |

| Clearcut | 5.6 | 3.6 |

| Pasture | 10.8 | 7.8 |

| Unclassified (Grazed) | 5.8 | 2.6(-)a |

| Nonuseableb | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Tree Size Class | ||

| Shrub-sampling | 7.0 | 6.4 |

| Pole | 16.3 | 10.1(-) |

| Medium saw timber | 36.0 | 54.1(+) |

| Large saw timber/pole | 15.0 | 13.2 |

| Large saw timber | 7.5 | 8.1 |

| Otherc | 18.2 | 8.1(-) |

| Tree Stocking Class | ||

| Poor | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Medium | 7.2 | 10.2 |

| Sparse/Well | 14.9 | 12.9 |

| Well | 51.7 | 62.4(+) |

| Otherc | 25.8 | 14.l(-) |

a (-) and (+) symbolize use significantly less than or greater than availability, respectively.

b nonuseable habitats include seed orchard, gravel or paved surfaces.

c Other habitats include unclassified or non-commercial forested lands.

Summer

High elevation summer ranges primarily consisted of Shasta red fir and mountain hemlock/red fir forests (Table 2). A variety of other less extensive forest types comprised the remainder of the composite home range. During both summers, elk used red fir forests less than expected on the basis of availability and mountain hemlock/red fir forests significantly more than expected. Although used less than availability, red fir forests still contained an average of 22% of all the elk observations on summer range and should, together with mountain hemlock/red fir, be considered important components of the park habitat. Such forests contain locally dense patches of smooth woodrush, which may be important elk forage on CRLA ranges (Hill 1974). A variety of lodgepole pine communities were selected or were used in proportion to availability and were important elk habitats in the southern part of the park.

| VEGETATION COVER CLASS | 1985 (N=160) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1986

(N=84)

AVAILABILITYUSEAVAILABILITYUSE

Brush0.40.60.50.0(-)Douglas-fir0.90.0(-)a1.10.0(-)Grass/Sedge0.10.00.10.0Lodgepole/Pumice7.25.07.67.1Lodgepole/Ponderosa5.411.9(+)a6.56.0Lodgepole/Red Fir/Mountain Hemlock4.08.14.78.3Mountain Hemlock5.44.44.66.0Mountain Hemlock/Red Fir28.551.9(+)29.341.7Ponderosa4.40.0(-)5.21.2Red Fir40.418.l(-)39.826.2(-)White Fir3.20.0(-)0.23.6Nonuseable0.40.0(-)0.40.0

a (-) and (+) symbolize use significantly less than or greater than availability, respectively.

Winter

Silviculturally managed forests in a variety of age- and size-classes made up more than 95% of the composited home range of elk in the Rogue Valley (Table 3). Clearcuts, less than 20 years old, primarily in the shrub-sapling developmental stage, comprised nearly 17% of the winter range. The pole stage of forest development, 21-60 years post-logging, made up 28% of the winter range. Pole stages corresponded to stands that were classed as either elk hiding cover or as hiding cover plus foraging area. A variety of sawlog and silviculturally overmature timber classes comprised the majority of the remaining winter range. Most of those forests were classed as elk thermal cover.

| VEGETATION CLASS | AVAILABILITY | USE |

|---|---|---|

| Elk Habitat Class | ||

| Foraging Area | 24.2 | 31.1 |

| Hiding Cover | 4.7 | 12.2(+)a |

| Hiding Cover/Forage | 25.2 | 30.5 |

| Thermal Cover | 37.6 | 19.5(-) |

| Optimal Cover | 0.3 | 6.1(+) |

| Otherb | 8.0 | 0.6(-) |

| Tree Size Class | ||

| Grass-Forb | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| Shrub-seedling (<0.9? dbh) | 16.9 | 21.3 |

| Pole (1.0 – 8.9? dbh) | 28.4 | 40.9(+) |

| Small sawlog (9.0 – 20.9? dbh) | 18.8 | 13.4 |

| Large sawlog (21.0? + dbh) | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Overmature (21.0? + dbh) | 29.3 | 22.0 |

| Otherb | 4.1 | 0.0(-) |

a (-) and (+) symbolize use significantly less than or greater than availability, respectively (p<0.l0)

b other habitats include unclassified or non-commercial forested lands.

Elk demonstrated a clear preference for both hiding cover and optimal cover on winter range. Optimal cover, so designated because it provides both optimum cover and foraging values during severe winter weather, made up a very small proportion of the winter range, but received high use by elk. The winter of this study was mild, and snow accumulations rarely exceeded more than 4? from December to spring. Optimal cover may have even greater importance as elk habitat during severe winters.

Foraging areas and stands of mixed hiding cover and foraging areas were neither preferred nor avoided by elk, but together they received high use (>60%). The close agreement between the availability (50%) and use (60%) of foraging areas by elk suggests that they may exist currently in a nearly optimum proportion of the winter range to satisfy forage requirements of the population. High preference of cover relative to forage, however, suggests that cover values may currently be more limiting to elk than forage. Creation of new foraging areas will be necessary to sustain wintering elk populations as the current foraging areas succeed to hiding and thermal cover. We suspect that the greatest challenge facing integrative forest and elk habitat management on this winter range in the future will be in providing replacement foraging areas without further diminishing important cover values.

Management Implications

Elk only occupy Crater Lake National Park during the summer. Thus other agencies such as The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and U.S. Forest Service have management responsibility for these elk and their habitat during the rest of the year. Summer habitat does not currently appear to be a limiting factor. Cow/calf ratios were quite high on the summer range, but substantial mortality may occur on the winter range.

There is no indication that elk populations have a significant impact on plant communities within CRLA. Elk are widely dispersed during the summer and, other than tracks, leave very little evidence of their presence. Furthermore, it is unlikely that populations will soon increase to levels which may cause impacts such as those documented in Mt. Rainier National Park (MORA). CRLA contains only limited areas of meadow which are most likely to show grazing or trampling impacts. Although we have no knowledge of primeval elk populations and habitat use patterns, we suspect that any changes in plant communities of CRLA are the result of factors other than elk, such as changes in fire frequency or climate.

Perhaps the greatest potential management concern is hunting. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife is currently experimenting with early hunting seasons to improve hunting quality. During these early seasons, elk are more dispersed and at higher elevation. Thus some elk, depending on snowfall, may remain in or near CRLA, or enter the park to avoid hunters. Although we don’t expect a “firing line” to develop, law enforcement could be more difficult. Any delay in migration should only be temporary because the seasons are relatively short and snow will eventually force elk out of the park. Therefore, park vegetation should not be significantly impacted. Depending on the timing and length of season, early hunting seasons may result in a reduced harvest of mature bulls. Throughout much of Oregon the proportion of older bulls has been greatly reduced by hunting. If harvest of these bulls was decreased in the Crater Lake region, sex and age structures of elk populations would more nearly resemble those typical of unhunted populations. Bulls with well developed antlers may be more commonly observed by park visitors.

Hunting by Native Americans would have a substantial potential for impact on CRLA elk. However, for the present, this doesn’t appear to be likely.

In conclusion, we see no need for further monitoring of elk within CRLA. However, cooperative work with ODFW, USFS, and the Klamath Tribe will help identify population trends. Surveys could best be conducted on the spring range, in late April or early May. Counts of elk occupying the meadows near Fort Klamath would provide an index of abundance. If elk populations were to increase significantly in the future, monitoring programs should be implemented within the park. Continued cooperation and communication with other concerned agencies may provide advance knowledge of management actions with potential for impact on CRLA elk.

Literature Cited

Dixon, K.R. and J.A. Chapman. 1980. Harmonic mean measure of animal activity area. Ecology 61:1040-1044.

Franklin, J.F. and C.T. Dyrness. 1973. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-8.

Harper, J.A. 1985. Ecology and management of Roosevelt elk in Oregon. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Portland, OR. 70 pp.

Hill, T. 1976. The ecology and management of Roosevelt elk in Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Unpubl. ms. on file at Crater Lake National Park.

Hopkins, W.E. 1979. Plant associations of the south Chiloquin and Klamath Ranger Districts – Winema National Forest. USDA For. Serv. PNW Region. R6-Ecol-79-005.

Jenkins, K.J. 1981. Status of elk populations and lowland habitats in western Olympic National Park. Cooperative Park Studies Unit, College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Report 81-1.

Kuttell, M.P. 1975. Willapa Hills elk herd. Washington Department of Game, Olympia, WA. 63 pp.

Manning, R. 1974. [Elk, their ecology and management. Unpubl. ins. on file at Crater Lake National Park.

Merrill, E.H., K.L. Knutson, B. Biswell, R.D. Taber, and K.J. Raedeke. 1985. Mount Saint Helens Cooperative Elk study: Progress Report 1981-84. Unpubl. ins.

Neu, C.W., C.R. Byers, and J.M. Peek. 1974. A technique for analysis of utilization-availability data. J. Wildl. Manage. 38:541-545.

Phillips, K.N. 1968. Hydrology of Crater, East and Davis Lakes, Oregon. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1859-E. 57 pp.

Smith, J.L. 1980. Reproductive rates, age structure, and management of Roosevelt elk in Washington’s Olympic Mountains. Pp. 67-111 in W. MacGregor (ed.). Proceedings of the Western States Elk Workshop. Feb. 27-28, 1980, Cranbrook, B.C.

Stuwe, M. and C.E. Blohowiak. Undated. MCPAAL: microcomputer programs for the analysis of animal locations. Unpubl. ins. available from Conservation and Research Center, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Walsh, S.J. 1977. An investigation into the comparative utility of color infrared aerial photography and LANDSAT data for detailed surface cover type mapping within Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Ph.D. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 356 pp.

Witmer, G.W. 1982. Roosevelt elk habitat use in the Oregon Coast Range. Ph.D. Thesis. Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 104 pp.

_____, et al. 1985. Deer and elk. Pp. 231-267 in E.R. Brown (ed.). Management of Wildlife and Fish Habitats in Forests of Western Oregon and Washington. USDA For. Serv. PNW Region.

Appendix A

Elk capture and response to drug administration in the Upper Klamath Basin, OR. 1985.

| DATE | SEX/AGE | COLLAR# | TRANSMITTOR FREQUENCY (MHZ) |

DOSAGE (MG) |

REACTION TIME (MIN) |

RECOVERY TIME (MIN) |

COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4/30/85 | ad. fem. | 1 | 151.500 | 18 | 11 | 27 | Nosebleed from trap |

| 5/3/85 | ad. fem. | 2 | 151.510 | 18 | 11 | 34 | |

| 5/4/85 | ad. fem. | –b | –b | 18 | 2 | Deceased at 8 min. Gash on jaw from trap | |

| 5/4/85 | ad. fem. | 4 | 151.530 | 18 | 5 | 29 | None |

| 5/13/85 | ad. fem. | 5 | 151.540 | 18 | 4 | 20 | |

| 5/25/85 | yr. male | –a | –a | 18 | 2 | 58 | Labored breathing |

| 5/25/85 | yr. male | –a | –a | 16 | 5 | 34 | |

| 5/27/85 | yr. fem. | 6 | 151.550 | 15 | 2 | 12 | Labored breathing |

| 5/28/85 | yr. fem. | 7 | 151.560 | 16 | 7 | 38 | |

| 5/31/85 | yr. male | –a | –a | 14 | 8 | 24 | |

| 5/31/85 | yr. fem. | 8 | 151.570 | 16 | 3 | 37 | |

| 6/11/85 | ad. fem. | –b | –b | 14 | 2 | 105 | Euthanized after 24 hrs. and no full recovery |

| 6/11/85 | ad. fem. | 9 | 151.580 | 18 | 6 | 17 | |

| 6/12/85 | ad. fem. | 11 | 151.600 | 18 | 5 | 19 | |

| 6/12/85 | ad. fem. | 12 | 151.610 | 18+18+20 | 5 | 38 | |

| 4/16/86 | ad. fem. | 18 | 5 | 25 | |||

| 5/14/86 | yr. fem. | –b | –b | 18 | — | — | Fractured skull |

a males were not radio-collared; equipped w/yellow ear streamers

b deceased

Other pages in this section

*** previous title *** --- *** next title ***