50-2 Volume 28 – 1997

Repeat Photography and Landscape Change

Introduction

The nature of nature is change. The physical and biological worlds in which we exist are constantly becoming different in myriad ways. A useful technique in comparing landscape changes occurring during a human lifetime and in analyzing long-term trends is repeat photography. Repeat photography is the art of locating the actual site of an old photograph, duplicating the position of the original camera and taking a repeat image of the same scene.

Background detail is critical in locating the position of the historic photo point and photographer. When possible, the same or similar film and camera type are used. A continuous record of change will result from frequent repeated photographs, documented with relevant information. This approach is an important part of monitoring protocol for interpreting the story of a landscape. Old photographs create much visitor interest, and with repeat photography, a better understanding of the natural processes operating in the landscape may be more easily communicated. Once resource management activities are implemented, such historical time-lapse photographs of changes are a baseline for future management proposals and actions.

The first known photograph of the Crater Lake caldera was taken by Peter Britt of Jacksonville in August 1874. Since then, Crater Lake has been the focus of many photographs. This allows for the comparison of known time interval photo pairs, which can establish a record of erosion rates and vegetation change in and near the caldera.

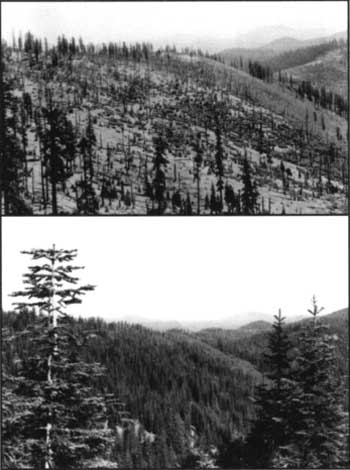

Some of the earliest photographic records of the park landscape away from the lake were during a vegetation survey of backcountry areas in 1936. These photographs have been useful in documenting tree encroachment into pumice fields and measuring cause-effect changes resulting from historical forest fires or sheep grazing that took place prior to the park’s establishment. Lodgepole pine encroachment into pumice fields, for example, began shortly before the 1936 photographs were taken. Reduced precipitation during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as minimal snowpacks for most of that period, extended the growing season significantly and allowed for successful conifer seedling establishment. An obvious change in forested landscapes has been the trend toward an increase in conifers, a shift away from herbaceous communities to those dominated by woody shrubs and trees. This is a common trend in western landscapes during the past century. Trends in vegetation change are driven by shifts in climatic factors and by human-induced disturbances such as Indian burning practices and recent fire suppression programs.

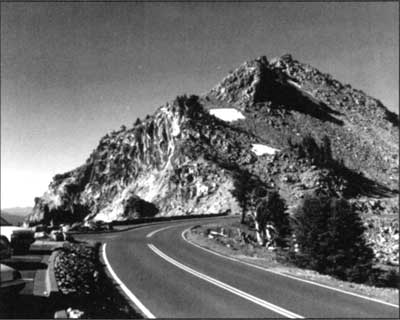

The Watchman in 1901 (top) and in August 1996 (bottom).

Top photo by J.S. Diller, U.S. Geological Survey.

Progress during 1996

Last year the Crater Lake Natural History Association made a grant to John Salinas and Dick Miller to produce a set of paired photographs. One black and white photograph in each set was to be a print of an image taken approximately 100 years earlier. This became possible when a large number of late 19th century photographs were found in the U.S. Geological Survey’s library in Denver. These photos had been snapped by J.S. Diller, a USGS geologist who can be credited with making the first scientific studies of Crater Lake beginning in l 883. Diller’s most important work, a professional paper on the park’s geology, appeared in 1902 — the same year that Crater Lake National Park was established. Many of the photos found in Denver were intended to illustrate his paper, though he used only a small fraction of them in the publication.

The current project began with Salinas and Miller spending hours pouring over copy prints and negatives which the National Park Service had recently acquired, in order to determine which ones might best show change in the landscape. A historic photograph was selected that has Garfield Peak as backdrop, so as to use Crater Lake Lodge as reference in the modern view. Another image showed the Watchman Overlook (on the west Rim Drive) without the fencing or parking lot. Diller’s photographs were also useful for studying change in the caldera. For example, historic views which include the lake are important to detect contrasts in the shoreline or caldera walls that become evident with time. Moreover, some of the photos repeated around Wizard Island illuminated the natural variability in lake levels and thereby demonstrated how that water body can be dynamic through time.

Two incidents in particular may help convey what it is like to set your boots in the precise footprint of an early photographer. In the first instance, it was mid afternoon on the crater rim of Wizard Island. The print held in the hands of repeat photographers clearly showed Llao Rock behind a bit of the rim with a whitebark pine growing out of a small mound of cinder covered by pinemat manzanita. There was only one place on the island where the crater and Llao Rock would match as in the photograph. But the whitebark pine was not to be seen. Like lightning, the realization that the pine was now a sun-bleached skeleton on the same small mound of cinder still covered with manzanita filled the repeat photographers with an almost surreal awe.

The site of the second incident was very easy to find since summer visitors take photographs from that spot every day. Something was not right, however, as Salinas viewed Victor Rock (where the Sinnott Memorial was built in 1930) from a point on the promenade where the Mather plaque is affixed. Somehow he needed to angle his camera a bit higher to take in more of the sky and less of the lake. Suddenly he realized that this point on the promenade was not the exact spot from where Diller had taken his photograph. The only way to replicate the historic image was to descend about 50 feet into the caldera. As one looks into the caldera from this point, it would be easy to imagine a photographer on that spot — but not Salinas. One slip on the loose pumice and that would be the end of this and several other projects. Consequently, the repeat photograph will have a slightly different angle.

Summit of cinder cone on Wizard Island, Crater Lake in 1901 (top) and today (bottom).

Top photo by J.S. Diller, U.S. Geological Survey; bottom photo by John Salinas.

Future work

Each person and every piece of equipment can be severely tested in this harsh environment. As the fallen mast of the Phantom Ship was being photographed from a tour boat making its rounds last summer, Salinas noticed an odd sound to the shutter on his large format (4 by 5 inch) camera. The shutter seemed to be hanging up after a cold night in the park. As it turned out, the same shutter failed to capture a dozen photographs around the lake and some from the top of Mount Scott. These photographs will have to be retaken during the summer of 1997 since the 1996 season ended without obtaining a complete set of repeat images. The project’s goal is to display copies of the original and repeat photographs in park exhibits and throughout a number of buildings. We hope this first attempt at repeat photography will lead to another project which will produce a book of large black and white paired photographs in time for the centennial of Crater Lake National Park in 2002.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Crater Lake Natural History Association’s sponsorship of this and other endeavors. The repeat photography project would not have been possible without discovery of the Diller photos by former seasonal interpreter Mike Smith and the assistance provided by USGS librarians in Denver.

Other pages in this section